“Despite unsuitable conditions of soft snow and high altitudes our Fergusons performed magnificently and it was their extreme reliability that made our trip to the pole possible.” —Telegram from Sir Edmund Hillary to Massey-Harris-Ferguson Farming Company

BY LAURA HARDIN | PHOTOS BY AP WORLDWIDE/RENNIE TAYLOR

Sir Edmund Hillary, right, and Jim Bates, both of New Zealand, stand before their tractors on Jan. 4, 1958, after arrival at the American Scientific Station at the South Pole. The party of five travelled 1,200 miles with this equipment over polar snow and ice. The square box at right was Hillary’s quarters and housed the expedition’s radio equipment.

As the coldest, windiest, driest and highest continent,Antarctica is the perfect setting for those looking for a challenge. So, when renowned New Zealand explorer Sir Edmund Hillary, the first man to conquer Mount Everest, was asked to join the Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition of 1955-58, he saw it as another grand adventure and chose Massey–Harris–Ferguson tractors to help get him there.

Led by Dr. Vivian Fuchs, the main objective of the British-led expedition was to be the first to travel overland in mechanized vehicles across the entire continent via the South Pole, gathering scientific data along the way. The main group would embark from the Weddell Sea coast of Antarctica (which is closest to South America), while a secondary New Zealand team, led by Hillary, would set out from the Ross Sea on the opposite side, establishing supply bases for the British team, but stopping short of the Pole. The two teams would meet up after the Brits had passed the Pole, with Hillary guiding them back along his path.

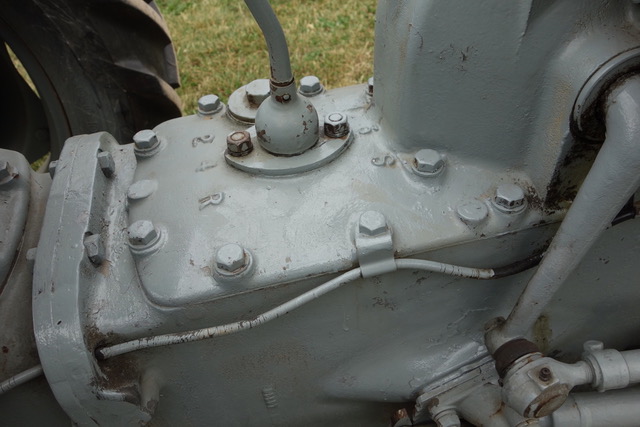

With more than 10 tons of fuel and supplies to carry, Hillary made an unlikely choice for his team’s main transport: farm tractors, specifically three Ferguson TE20s. Given some modifications to better equip them for the extreme conditions, Hillary was confident his tractors were up for the challenge—and then some.

On October 14, 1957, Hillary’s team cranked up its caravan of Fergusons and a support vehicle, pulling a bunkhouse and several supply sleds. Even though it was the Antarctic summer, conditions were brutal. Over the next 82 days, they faced temperatures below -35º Celsius, winds above 50 knots and altitudes surpassing 10,000 feet.

Even in such extreme conditions, the Hillary team reached its destination on December 15. Once there, they learned the British team—which, incidentally, was using more high-tech snow vehicles—was significantly behind schedule and would not reach the New Zealanders for about another month. Hillary decided not to wait and continued on to the South Pole to meet the rest of the expedition there.

To great fanfare, Hillary’s team reached the U.S. Pole Station on January 4, 1958. Before heading into the warmth of the station, he paused and later wrote, “I took a last glance at our tractor train … our Fergusons had brought us over 1,250 miles of snow and ice, crevasse … soft snow and blizzard to be the first vehicles to drive to the South Pole.”

Sir Edmund Hillary, Derek Wright and Murray Ellis arriving at the South Pole in their Ferguson tractors on 4 January 1958.

Sir Edmund Hillary leads New Zealand party to the Pole

On 4 January 1958 Sir Edmund Hillary and his New Zealand party reached the South Pole. They were the first to do so overland since Scott in 1912, and the first to reach it in motor vehicles. The party set out for the Pole after laying food and fuel depots for the British crossing party of the Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition (TAE). It was an arduous journey – long hours were spent battling through sastrugi (wind-eroded snow ridges), soft snow and dangerous crevasses. But what is often remembered is Hillary’s determination to proceed with the journey without the express permission of the TAE, and against the instructions of the committee coordinating New Zealand’s contribution.

Discussions with Sir Vivian Fuchs and the Ross Sea Committee

In July 1955, just a month after being appointed to lead the New Zealand component of the TAE, Hillary raised the idea of carrying on to the Pole with the expedition’s overall commander, British explorer Dr Vivian Fuchs. At this time neither Fuchs nor the Ross Sea Committee, which was coordinating New Zealand’s contribution, raised any objection. But in a series of phone calls and telegrams in early 1957 the Executive of the Ross Sea Committee cautioned Hillary against continuing on to the Pole without Fuchs’ express permission. They also knocked back his ambitious plans for the New Zealand parties over the spring and summer. Hillary was surprised, but had not sought the Committee’s permission for his activities and so did not see their response as an obstacle. In his autobiography, Nothing venture, nothing win, he commented:

I continued as though the exchange of messages had never occurred … It was becoming clear to me that a supporting role was not my particular strength. Once we had done all that was asked of us – and a good bit more – I could see no reason why we shouldn’t be organising a few interesting challenges for ourselves.

NZ party sets out to lay food and fuel depots

The Pole journey was still firmly in Hillary’s mind when the southern party set out from Scott Base on 14 October 1957 to lay food and fuel depots. In November, as the party neared the site of Depot 480, Hillary received another surprising message from the Ross Sea Committee. This time the full Committee had met and indicated that they would give their support to the Pole journey following formal approval from London. Hillary later claimed to have misread the message – taking it that formal approval had already been given.

Shortly after the party reached Depot 480 Hillary advised the Committee that they intended continuing south towards Fuchs after laying their final depot, Depot 700. If he didn’t require their vehicles, they would continue on to the Pole. The Executive Committee instructed him not to leave the final depot unmanned. The party continued on as planned to Depot 700. Shortly after arriving on 15 December they received a message indicating Fuchs would arrive at the Pole between Christmas and the New Year. As the depot neared completion Hillary advised Fuchs and the Committee that his party intended pressing further south to mark a path through the crevassed areas.

Dash to the Pole begins

At 8.30 p.m. on 20 December the party, at this point made up of Hillary, Murray Ellis, Peter Mulgrew, Jim Bates and Derek Wright, began what has been described as the final ‘dash to the pole’. When they stopped at 6 a.m. on 21 December Hillary received yet another message from the Committee insisting they stay at Depot 700. Again he ignored their request. But he did alert Fuchs and noted that his plan to continue to the Pole could be abandoned if Fuchs needed their assistance. On 24 December the party received a reassuring Christmas message from Fuchs in which he approved of them marking the path further south. Hillary responded with further news of their progress, then waited another day before proceeding further south. It wasn’t until 28 December that Fuchs, concerned that his party might run out of fuel, asked Hillary to abandon the bid for the Pole and lay another depot. But by then it was too late. Hillary replied that they had insufficient food or fuel to lay an additional depot or to return to Depot 700 and await his arrival, which had been significantly delayed. Hillary arranged for more fuel to be taken to Depot 700 and then continued the journey south.

Ferguson tractors

The party completed their journey to the Pole in three converted Ferguson tractors with ‘windshields but no roofs’. Hillary’s official biographer, Alexa Johnston, has likened the journey to driving ‘across Antarctica in convertibles’. Two sledges and a caboose – essentially a caravan on skis – containing bunks, cooking and radio facilities, also survived the journey to the Pole.

Arrival at the Pole

After 14 days battling through sastrugi, soft snow and crevasses, the party finally sighted the South Pole at 8 p.m. on 3 January 1958. They were exhausted, having slept for only a few hours at a time since leaving Scott Base. So after sending off the code word ‘Rhubarb’ to indicate they had the Pole in sight, they went to sleep. They completed the final part of the journey the next morning, arriving at the South Pole station at 12.30 p.m.

As the party was being congratulated on reaching the Pole, the media abroad began to question whether Hillary’s decision had put the entire expedition at risk. Speculation of a rift between Fuchs and Hillary only increased after news reached the media that Hillary, concerned that Fuchs’ party was running well behind schedule, had suggested he abandon the crossing and return the following year. But when Fuchs met Hillary at the South Pole on 20 January there was no evidence of animosity between the pair – Fuchs’ first words to Hillary were ‘Damned glad to see you, Ed’. In the days that followed Fuchs called on Hillary’s knowledge of the terrain between the Pole and Scott Base to bring the crossing to a safe conclusion. Fuchs’ party arrived at Scott Base on 2 March 1958, having completed the first successful trans-Antarctic crossing.

In an interview with Time magazine in 2003, Hillary compared his experience in the Antarctic to his experience climbing Everest:

Oh, no [it wasn’t harder than Everest]. It was different in many different ways. The problems of snow and ice were similar, but on a big mountain like Everest, there were more immediate dangers – the possibility of avalanche or falling off the mountain or going down a crevasse. In the Antarctic, the temperatures on the whole were colder, the distances were vast and it was a much longer sort of business, really. So in our trip to the South Pole, we were under constant tension, for long, long periods. For hours we’d be under great tension. Whereas on a big mountain it would be for short periods.

Further information

Books

- Pat Booth, Edmund Hillary: the life of a legend, Moa Beckett Publishers Limited, Auckland, 1993

- David L. Harrowfield, Call of the Ice: Fifty years of New Zealand in Antarctica, David Bateman Ltd, Auckland, 2007

- Alexa Johnston, Sir Edmund Hillary: an extraordinary life, Penguin Books, Auckland, 2006

- A S Helm and J H Miller, Antarctica, R. E. Owen, Government Printer, Wellington, 1964

- Edmund Hillary, Nothing venture, nothing win, Hodder and Stoughton Limited, London, 1975

- Geoffrey Lee Martin, Hellbent for the Pole, Random House New Zealand, Auckland, 2007

- L. B. Quartermain, New Zealand and the Antarctic, A R Shearer, Government Printer, Wellington, 1971

Links

e

Arrival at the Pole by tractor

Arrival at the Pole by tractor