“The Song of the Shirt” Themes

With fingers weary and worn,

2With eyelids heavy and red,

3A woman sat, in unwomanly rags,

4Plying her needle and thread—

5Stitch! stitch! stitch!

6In poverty, hunger, and dirt,

7And still with a voice of dolorous pitch

8She sang the “Song of the Shirt.”

9“Work! work! work!

10While the cock is crowing aloof!

11And work—work—work,

12Till the stars shine through the roof!

13It’s O! to be a slave

14Along with the barbarous Turk,

15Where woman has never a soul to save,

16If this is Christian work!

17“Work—work—work

18Till the brain begins to swim;

19Work—work—work

20Till the eyes are heavy and dim!

21Seam, and gusset, and band,

22Band, and gusset, and seam,

23Till over the buttons I fall asleep,

24And sew them on in a dream!

25“O, Men, with Sisters dear!

26O, Men! with Mothers and Wives!

27It is not linen you’re wearing out,

28But human creatures’ lives!

29Stitch—stitch—stitch,

30In poverty, hunger, and dirt,

31Sewing at once with a double thread,

32A Shroud as well as a Shirt.

33“But why do I talk of Death?

34That Phantom of grisly bone,

35I hardly fear its terrible shape,

36It seems so like my own—

37It seems so like my own,

38Because of the fasts I keep;

39Oh! God! that bread should be so dear,

40And flesh and blood so cheap!

41“Work—work—work!

42My Labour never flags;

43And what are its wages? A bed of straw,

44A crust of bread—and rags.

45That shatter’d roof—and this naked floor—

46A table—a broken chair—

47And a wall so blank, my shadow I thank

48For sometimes falling there!

49“Work—work—work!

50From weary chime to chime,

51Work—work—work!

52As prisoners work for crime!

53Band, and gusset, and seam,

54Seam, and gusset, and band,

55Till the heart is sick, and the brain benumb’d,

56As well as the weary hand.

57“Work—work—work,

58In the dull December light,

59And work—work—work,

60When the weather is warm and bright—

61While underneath the eaves

62The brooding swallows cling

63As if to show me their sunny backs

64And twit me with the spring.

65“O! but to breathe the breath

66Of the cowslip and primrose sweet—

67With the sky above my head,

68And the grass beneath my feet

69For only one short hour

70To feel as I used to feel,

71Before I knew the woes of want

72And the walk that costs a meal!

73“O! but for one short hour!

74A respite however brief!

75No blessed leisure for Love or Hope,

76But only time for Grief!

77A little weeping would ease my heart,

78But in their briny bed

79My tears must stop, for every drop

80Hinders needle and thread!”

81With fingers weary and worn,

82With eyelids heavy and red,

83A woman sat in unwomanly rags,

84Plying her needle and thread—

85Stitch! stitch! stitch!

86In poverty, hunger, and dirt,

87And still with a voice of dolorous pitch,—

88Would that its tone could reach the Rich!—

89She sang this “Song of the Shirt!”

” data-highlight-when-focused=”true” data-modal-title=”Theme” data-position=”1″ data-title=”Poverty and Labor in Victorian England” style=”box-sizing: border-box; border-radius: 3px 3px 3px 0px; padding-bottom: 1em;”>

Poverty and Labor in Victorian England

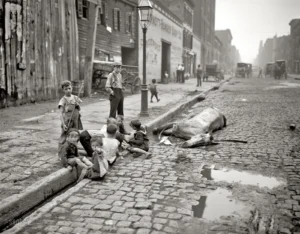

“The Song of the Shirt” spotlights the experiences of Victorian England’s working poor. The subject of the poem is a seamstress who works ceaselessly in inhumane, even torturous conditions simply to get by. This unending labor fills her with deep despair and hopelessness, even as “the Rich” remain oblivious to these struggles of the working class. Through the woman’s song, the poem seeks to expose the burdens of poverty and the dehumanizing labor conditions faced by poor workers in 19th-century England.

The seamstress’s song emphasizes the repetitive, monotonous, and utterly exhausting nature of her labor. She complains that she works from morning, when the rooster crows, to night, when the stars shine, and that all day she can’t take even “one short hour” of rest. She doesn’t even have time to cry, she sings, because crying will slow her work. Ultimately, the seamstress works so long that she falls asleep over the buttons she sews, only to then keep on working “in a dream.”

All this work takes an immense physical and mental toll on the seamstress. Her fingers are “weary and worn” while her “eyelids [are] heavy and red.” She feels like the “brooding swallows” outside taunt her, singing that they “twit me with the spring”—mocking her while she’s trapped inside her “blank” and unpleasant room. Her heart and mind, meanwhile, have grown “sick” and numb. Working to survive is, ironically, draining the seamstress of her very life: she says that she’s “Sewing at once, with a double thread, / A Shroud as well as a Shirt”—in other words, preparing for her own funeral—and beginning to look like the “terrible shape” of death itself.

The seamstress’s misery, the poem implies, is the product of a society that values human life less than material goods—that treats “flesh and blood” as “cheap.” Those who buy her clothes pay no heed to the fact that it’s “not linen” they’re “wearing out” but rather “human creatures’ lives”—in other words, they don’t know or care that they’re benefitting from the torturous, endless labor of people in poverty. The seamstress even compares herself to a “slave,” indicating that she feels like society treats her as sub-human. Instead, she is a “creature” or a “prisoner” without “a soul to save.”

By recording the seamstress’s song, the speaker of “The Song of the Shirt” thus exposes how miserable, dirty, and inhumane life can be for the working poor. Writing at the end, “Would that its tone could reach the Rich,” the speaker suggests that if others only listened to and cared about the seamstress, they might realize that people like her need—and indeed deserve—relief from the torments of poverty.

1With fingers weary and worn,

2With eyelids heavy and red,

3A woman sat, in unwomanly rags,

4Plying her needle and thread—

5Stitch! stitch! stitch!

6In poverty, hunger, and dirt,

7And still with a voice of dolorous pitch

8She sang the “Song of the Shirt.”

9“Work! work! work!

10While the cock is crowing aloof!

11And work—work—work,

12Till the stars shine through the roof!

13It’s O! to be a slave

14Along with the barbarous Turk,

15Where woman has never a soul to save,

16If this is Christian work!

17“Work—work—work

18Till the brain begins to swim;

19Work—work—work

20Till the eyes are heavy and dim!

21Seam, and gusset, and band,

22Band, and gusset, and seam,

23Till over the buttons I fall asleep,

24And sew them on in a dream!

25“O, Men, with Sisters dear!

26O, Men! with Mothers and Wives!

27It is not linen you’re wearing out,

28But human creatures’ lives!

29Stitch—stitch—stitch,

30In poverty, hunger, and dirt,

31Sewing at once with a double thread,

32A Shroud as well as a Shirt.

33“But why do I talk of Death?

34That Phantom of grisly bone,

35I hardly fear its terrible shape,

36It seems so like my own—

37It seems so like my own,

38Because of the fasts I keep;

39Oh! God! that bread should be so dear,

40And flesh and blood so cheap!

41“Work—work—work!

42My Labour never flags;

43And what are its wages? A bed of straw,

44A crust of bread—and rags.

45That shatter’d roof—and this naked floor—

46A table—a broken chair—

47And a wall so blank, my shadow I thank

48For sometimes falling there!

49“Work—work—work!

50From weary chime to chime,

51Work—work—work!

52As prisoners work for crime!

53Band, and gusset, and seam,

54Seam, and gusset, and band,

55Till the heart is sick, and the brain benumb’d,

56As well as the weary hand.

57“Work—work—work,

58In the dull December light,

59And work—work—work,

60When the weather is warm and bright—

61While underneath the eaves

62The brooding swallows cling

63As if to show me their sunny backs

64And twit me with the spring.

65“O! but to breathe the breath

66Of the cowslip and primrose sweet—

67With the sky above my head,

68And the grass beneath my feet

69For only one short hour

70To feel as I used to feel,

71Before I knew the woes of want

72And the walk that costs a meal!

73“O! but for one short hour!

74A respite however brief!

75No blessed leisure for Love or Hope,

76But only time for Grief!

77A little weeping would ease my heart,

78But in their briny bed

79My tears must stop, for every drop

80Hinders needle and thread!”

81With fingers weary and worn,

82With eyelids heavy and red,

83A woman sat in unwomanly rags,

84Plying her needle and thread—

85Stitch! stitch! stitch!

86In poverty, hunger, and dirt,

87And still with a voice of dolorous pitch,—

88Would that its tone could reach the Rich!—

89She sang this “Song of the Shirt!”

” data-highlight-when-focused=”true” data-modal-title=”Theme” data-position=”2″ data-title=”Gender Inequality in Victorian England” style=”box-sizing: border-box; border-radius: 3px 3px 3px 0px; padding-bottom: 2em;”>

Gender Inequality in Victorian England

The poor seamstress at the heart of “The Song of the Shirt” believes that her life is all the more difficult because she is a woman struggling to provide for herself in a society that devalues women’s labor. While the poem predominantly focuses on the burdens of poverty in general, Hood also suggests that those burdens are distributed unequally; Victorian society placed a premium on traditional femininity (especially physical beauty, grace, and obedience) and granted women fewer opportunities to become independent or self-sufficient—making it all the more difficult for those women who had to work to support themselves and their families.

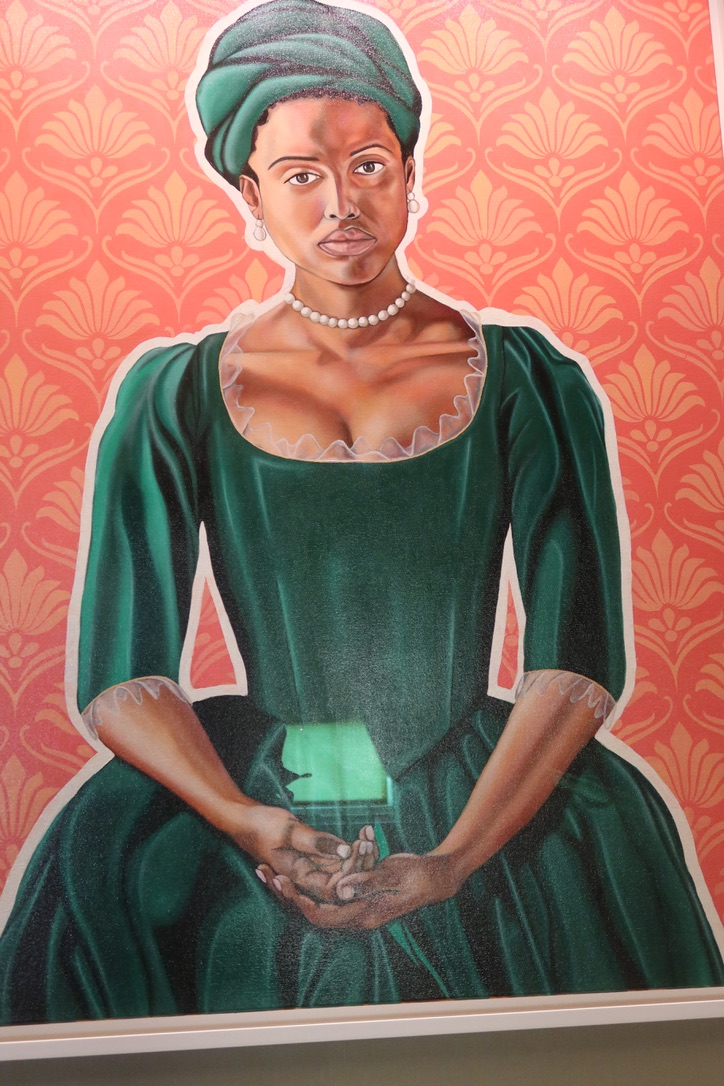

The subject of the poem toils over the kind of work (sewing clothing by hand) that many poverty-stricken women had to perform to survive in the 19th century. Hood in fact wrote the poem in honor of a widow named Mrs. Biddell, who sewed clothes and pawned the clothing she made in order to feed her starving children. The seamstress in the poem likewise constantly works her “needle and thread,” obsessing over “seam, and gusset, and band,” because this is the only way she can support herself. The seamstress doesn’t mention if she has children, but she does blame men for burdening her and other women with this tedious work, crying, “O, men, with sisters dear! / O, men, with mothers and wives!” She suggests that while women must work to feed their families, men often don’t realize—or care—how much their wives and sisters suffer as a result of these burdens.

Because she works so hard, slaving over needle and thread, the seamstress seems to lose what makes her a woman. In the first and last stanzas, the speaker describes the seamstress as a “woman” in “unwomanly rags.” The seamstress obviously can’t take care of her physical appearance: she can hardly feed herself, let alone try to look “womanly.” The seamstress also complains that her work makes her feel like less than a woman—indeed, less than a human being. She claims that “human creatures’ lives” get worn out by these horrible, impoverished conditions. Lack of food and rest make the seamstress look like death itself, a “phantom of grisly bone.” Evidently, the physical toll of the seamstress’s work is almost more than she can endure.

Ultimately, “The Song of the Shirt” demonstrates that very poor women must bear such extreme burdens that they cease to really be women at all (in a Victorian sense of the word, that is), becoming instead “benumbed” and “weary” slaves.

B

B

bloximages.chicago2.vip.townnews.com/theifp.ca/content/tncms/assets/v3/editorial/d/59/d599fc38-8651-5682-ad77-738a894ec0ad/63de34ed43a5a.image.jpg?resize=200%2C150 200w,

bloximages.chicago2.vip.townnews.com/theifp.ca/content/tncms/assets/v3/editorial/d/59/d599fc38-8651-5682-ad77-738a894ec0ad/63de34ed43a5a.image.jpg?resize=200%2C150 200w,