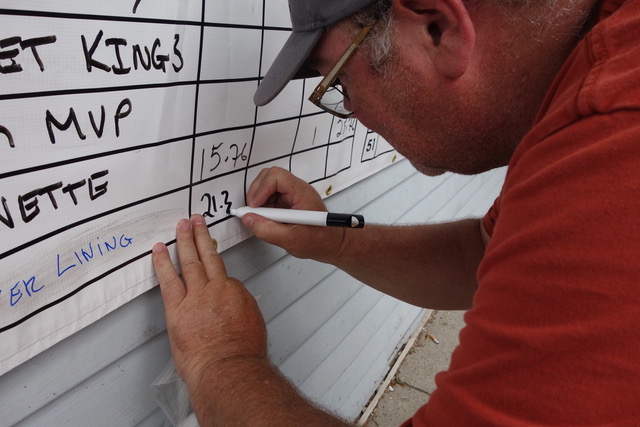

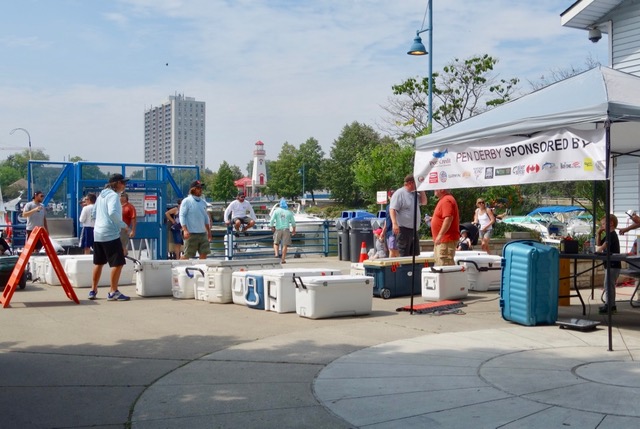

Sure enough. At noon the harbour was bubbling with fish boats and happy

fishermen. IT WAS TIME TO SEE WHO GOT THE BIGGEST SALMON.

This Chinook Pacific salmon is swimming in all the GreAT Lakes…voracious creature. A CHINOOK SALMON.

I bet dollars to donuts that few of you have ever heard of Howard Tanner. He changed the Great Lakes and nobody around me today seems to be

aware of what happened back in 1966 when Howard Tanner played fast and loose with our Great Lakes by ‘seeding’ Lake Michigan with baby salmon from the

Pacific Ocean. Coho and Chinook Salmon. Voracious predators that gobble up alewives like there is no tomorrow.

“When our 50 boatloads of fishermen hit the dock…everyone nearby will know what lurks out there..”

“Who could believe that these huge creatures are chomping on alewives just s few kilometres out in the lake?”

“Because these gigantic creatures spend most of their lives in water that is 100 to 200 feet deep. Dark down there…perfect

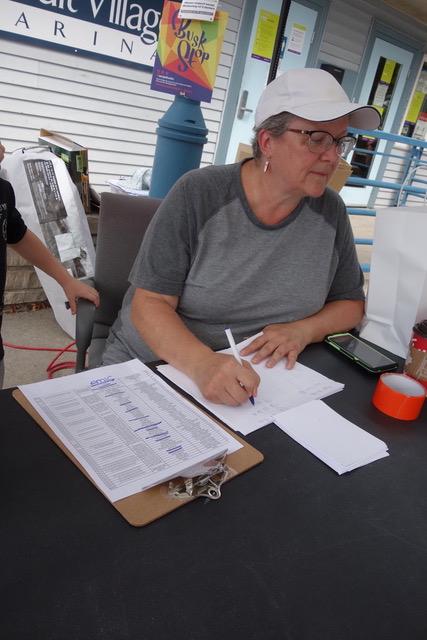

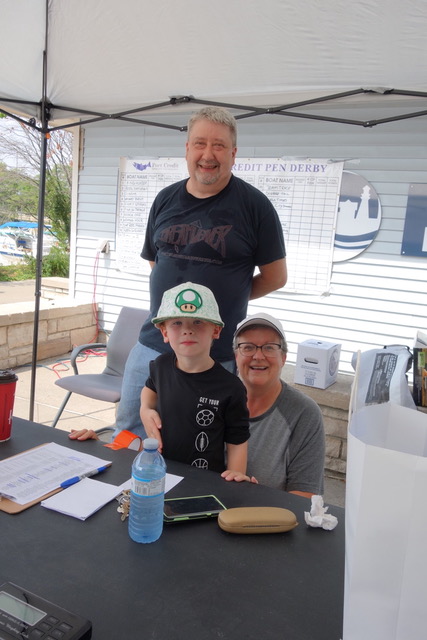

There he is now. Andrew Skeoch and two fishing brothers.

Andrew Skeoch describes the salmon caught today…a contender for the big money prize at the

Port Credit fish Derby. His morher, Marjorie, is suitably impressed.

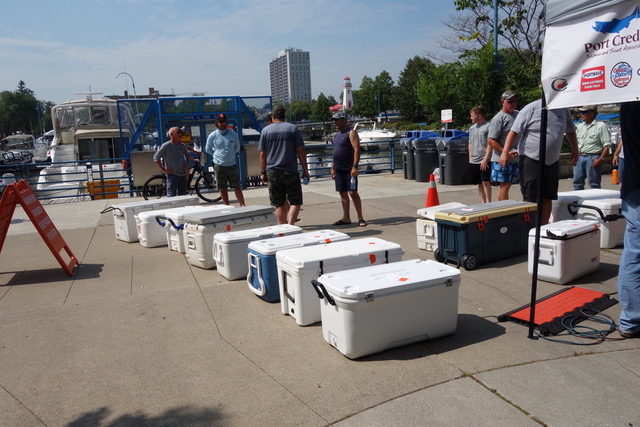

These fish coffins needed two men to carry.

a Snakehead. Snakehead? Yes, There are other creatures starting to creep into our waters.

Another story.

HOW DID PACIFIC SALMON…CHINOOK AND COHO…BECOME THE TOP PREDATOR FISH IN THE GREAT LAKES?

HOWARD TANNER…DID IT IN 1966…55 years ago.

STOCKING THE GREAT LAKES WITH PACIFIC SALMON WAS AN EXPERIMENT IN 1966. TODAY, AUGUST 2021, THE EXPERIMENT IS AN OBVIOUS SUCCESS.

o be clear, what Howard Tanner was now contemplating was nothing less than the intentional introduction of a non-native Pacific species to the largest freshwater system in the world. And when he worked up the nerve to start speaking publicly about his idea, people were quick to raise concerns. First and foremost, no fisheries biologist had ever attempted to manage water even close to this size. In Tanner’s case, his master’s degree program had put him in charge of a 27-acre lake; his doctoral program, six lakes—the largest of which was six acres. Lake Michigan alone was 23 million acres. “It was like somebody who had gotten good at raising geraniums in flower pots was now being given a cattle ranch,” Tanner says.

There were also logistical questions. Some argued salmon would die in freshwater or simply head into the St. Lawrence River and out to the open ocean. Others pointed to the many failed attempts to introduce salmon to the Great Lakes dating back to the late 1800s. The plan also faced one giant, undeniable obstacle: coho salmon, the fish that Tanner had identified as the species of choice, simply couldn’t be had. At the time, every single coho egg harvested from the hatcheries of Oregon and Washington were spoken for—part of a grand attempt to re-establish salmon in the heavily dammed Columbia River.

Then came the phone call.

Howard Tanner was sitting in his living room, having his usual pre-dinner cocktail. On the line was one of his old Western colleagues. He was calling to let Tanner know there was an anticipated surplus of coho eggs on the West Coast.

“It was just like the chair fell from under me,” Tanner remembers. “That night, I didn’t sleep much. I just sat there most of the night, thinking, What if … What if?”

The following morning, he was in his office watching the clock tick. With a three-hour difference between Michigan and the coast, he had to wait until midday to confirm the rumors that coho were available. The hearsay turned out to be true. Still, to get some of the eggs, he and his contacts in Oregon would have to navigate a gauntlet of bureaucracy. On top of that, they were working with an immovable biological deadline: If the surplus coho eggs were going to be viable for hatching and release back in Michigan, the whole plan would have to get every bureaucratic stamp in no more than six weeks. But, in a scenario Tanner can characterize only with words like “miracle,” the approvals came. Within a few weeks, one million coho salmon eggs were on a plane, bound for the Great Lakes. Tanner’s spectacular experiment was now underway.

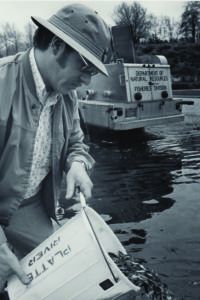

Everything happened so fast that Tanner didn’t yet have money for things like fish food. And he didn’t know exactly where he was going to raise the fish once they hatched. Michigan’s hatchery system, which had been largely devoted to restoring lake trout, was 40 years out of date and in no shape to undertake a program of this size. He went to the legislature and asked for a million dollars—half of which he finally won by promising the chair of the Senate Appropriations Committee that 150,000 of the salmon (and the promised economic boom) would land in the senator’s district. Tanner and his team then embarked on a tour of the state’s hatchery system, looking for just the right place to raise the fish. Eventually, the hatchery on the modest Platte River in

Benzie County was chosen as the spot where the salmon would start their lives—and, theoretically, return to spawn—if everything went according to plan.

Tanner remembers the moment when the fish were finally ready to be

released as one of the great moments of his career. It was April 2, 1966, and the now year-and-a-half-old coho were ready to enter the Platte River near

Honor, Michigan. He had a special wooden speaker’s platform built for the event. Public officials offered words touting the benefits of the salmon program. The press took photos. Then, Arnell Engstrom, the

Traverse City house representative whose vote had been critical in funding the salmon program, picked up a golden bucket and dumped the first batch into the Lake Michigan watershed. Tanner got his turn later in the afternoon on Bear Creek, a tributary of the Manistee, at a site just below Tippy Dam. Swimming with the current, the four-inch “smolts” would find their way to the open water in less than two days.

If everything went according to plan, the young coho would spend a year and a half in the open water before returning to the Platte River in the fall of 1967. And early indications suggested the fish would indeed find their way home. In the fall of 1966, the “Jack” salmon—a small class of precocious fish that spawn a year ahead of schedule—started showing up in Platte Bay, many in a form that astonished Tanner’s Western colleagues and foreshadowed a potentially colossal spawning run the following year. “On the coast, the Jack will maybe weigh a pound and a half or two pounds,” Tanner says. “Some of our fish were coming back at seven pounds. The guys from Oregon just shook their heads and said, ‘You’d better get ready. You’d better get ready.’ ”

Even today, what happened next still stands as the biggest “big fish” story in Great Lakes history. In late August 1967, tens of thousands of returning salmon suddenly announced their presence—this time without a formal speech. coho rushed into Platte Bay, and the fishermen followed—largely learning of the spectacle by word of mouth. Tanner has aerial photos from that fall showing tiny Platte Bay jammed with 3,000-plus boats, many of them canoes and little aluminum dinghies not suitable for open water. The boats formed a near-solid mass; some fishermen joked you could almost walk from boat to boat and never get wet. And in between, the fish were so thick, they were porpoising out of the water.

Tiny coastal towns like Honor, Empire and

Frankfo

rt suddenly found themselves overrun with tens of thousands of fishermen and wannabe fishermen. The tiny boat launches grew tails of cars and trailers that ran miles long. One man, Tanner remembers, even started a taxi service to ferry people back and forth. Another guy was selling hot dogs. Lures sold out, so people started renting lures. In September, Sports Illustrated even showed up to cover the event they dubbed a “boom on Lake Michigan.”

People who had never caught any fish of any size like these were catching five, and their tiny little boats were just full of salmon. Nobody had to embellish the stories. It was madness.

The impacts of the salmon were huge and immediate. The value of riparian property in the surrounding area doubled almost instantly. Hotels and businesses sprouted up in Michigan’s new salmon country. Tiny Honor, Michigan, population 300, even christened itself the state’s new “Coho Capital.” The joyful hysteria was only briefly interrupted by tragedy on September 23, when the crush of mostly inexperienced anglers ignored small-craft warnings and found themselves overrun by a violent Lake Michigan storm. One hundred fifty boats were swamped; seven people drowned. But it hardly blunted the public’s appetite for salmon. Now, every coastal town’s bait shop and city hall were lobbying for the fish to be planted in the local stream. And the state delivered, stocking millions more coho across the rest of the Great Lakes in the following years, and furiously expanding the antiquated hatchery system to give the people what they wanted.

Doubling down on its great salmon experiment, the state added an even bigger trophy to the mix of Great Lakes fish the following year. The Chinook salmon was a Pacific species two to three times bigger than the coho, was cheaper to produce, and had a diet that consisted almost exclusively of the hated alewife. Within a few years of the new super-salmon hitting the open water, reeling in a 30-pounder became common. Fishermen loved it. Sunbathers loved the fact that alewives weren’t rotting on their beaches. And the fisheries department kept the big fish coming, flooding the Great Lakes with millions of coho and Chinook every year—the state’s economy, in turn, flooding with the windfalls of a world-class fishery that seemed to have been created overnight.

“It almost gave us the impression that the system was unlimited,” says Randy Claramunt, a fisheries research biologist with the Michigan Department of Natural Resources. “The more salmon we put in, the more salmon we got out. Literally, we went from zero stocking to almost eight million a year in the 1980s, and we still had record-high harvest levels.”

By the mid-1980s, there was no arguing that Tanner’s original vision had indeed evolved into something worthy of the word “spectacular.” Just two decades after his coho fingerlings were released into the Platte River, the salmon had brought under control one of the area’s worst invaders, alewives. The sport-fishing industry, previously non-existent, was now valued in the billions of dollars. And people came from all over the country to fish the Great Lakes.

But the record catches and the new trickle-down salmon economy in which everyone seemed a winner weren’t telling the whole story. Though no one knew it at the time, the Lake Michigan fishery, the crown jewel of the lakes, was beginning to strain. The system did indeed have limits. And without warning, the once-mighty Chinook, the adopted king of Michigan waters, all but vanished almost as quickly as it appeared.

In a plot twist worthy of the theater, it was the demise of the fish everybody hated that brought down the fish everybody loved. The alewife—the invasive saltwater species that was best known for dying and rotting en masse on Michigan beaches—had given the Chinook salmon what seemed like an endless food supply. In fact, when the salmon program was first conceived, it was never done so as an alewife control program; the small invaders were so prolific that the idea that their populations could be significantly impacted by a predator seemed like wishful thinking.

In less than two decades, however, the Chinook began to chip away at the alewife’s dominance. In fact, by the early 1980s, alewife biomass in the Great Lakes stood at less than 20 percent of historic highs—largely because of salmon predation. With less to eat, the salmon being reeled in from the lakes started to get smaller and thinner. Then, in the mid-1980s, the already-stressed Chinook was overcome by an outbreak of a mysterious kidney disease, one that would later be linked to the high-density hatcheries unknowingly pushing out diseased fish to keep up with the public’s demand for salmon. Though the less-fished and more-adaptable coho toughed it out, the mighty Chinook soon disappeared from Lake Michigan.

More than a decade later, the story repeated itself in Lake Huron in an even more devastating fashion. Better rates of natural reproduction and heavy stocking led to a scenario in which the Chinook ate themselves out of an ecosystem. To make matters worse, new invasive species like the zebra and quagga mussels—both of which filtered plankton out of the lake—undermined the alewives’ own food supply. Faced with pressure from both the bottom and top of the food chain, the alewife population collapsed in the early 2000s, the Chinook population following close behind. Stories of big fish harvested from Lake Huron were quickly replaced by those of gas stations, hotels and restaurants going belly-up. There were even stories about charter boat fishermen moving west to try to start over on the Lake Michigan side, where salmon populations had started to rebound.

The salmon bust revealed new truths that had gradually become latent fundamentals of the salmon program. For one, if the state was going to maintain salmon as a top predator in the Great Lakes, it needed a more nuanced policy than raising as many fish as it could and dumping them into the water. It was also obvious now that the salmon economy had grown too big to fail: The experiment that Howard Tanner had started almost on a hunch had now evolved into a $7 billion economy and a vital tool for restoring balance to the largest freshwater system in the world. More importantly, though, the salmon program had inadvertently ushered in an era whereby the Great Lakes would now be a highly managed entity, and from which there was no turning back.

released as one of the great moments of his career. It was April 2, 1966, and the now year-and-a-half-old coho were ready to enter the Platte River near Honor, Michigan. He had a special wooden speaker’s platform built for the event. Public officials offered words touting the benefits of the salmon program. The press took photos. Then, Arnell Engstrom, the Traverse City house representative whose vote had been critical in funding the salmon program, picked up a golden bucket and dumped the first batch into the Lake Michigan watershed. Tanner got his turn later in the afternoon on Bear Creek, a tributary of the Manistee, at a site just below Tippy Dam. Swimming with the current, the four-inch “smolts” would find their way to the open water in less than two days.

released as one of the great moments of his career. It was April 2, 1966, and the now year-and-a-half-old coho were ready to enter the Platte River near Honor, Michigan. He had a special wooden speaker’s platform built for the event. Public officials offered words touting the benefits of the salmon program. The press took photos. Then, Arnell Engstrom, the Traverse City house representative whose vote had been critical in funding the salmon program, picked up a golden bucket and dumped the first batch into the Lake Michigan watershed. Tanner got his turn later in the afternoon on Bear Creek, a tributary of the Manistee, at a site just below Tippy Dam. Swimming with the current, the four-inch “smolts” would find their way to the open water in less than two days.