EPISODE 327 JANUARY 1, 1993: BREAK UP OF CZECHOSLOVAKIA INTO CZECH AND SLOVAK REPUBLICS

EPISODE 327 JAN. 1, 1993 THE YEAR CZECHOSLOVAKIA DISAPPEARED…CEASED TO EXIST

alan skeoch

May 1, 2021

A STARTLING AND UNFORGETTABLE MARCH HOLIDAY WEEK….1993

“Mom and dad, why don’t you fly over here on the March School break?”

“Is it safe?”

“Perfectly safe.”

“We read that Czechoslovakia is splitting…sounds like Civil War.”

“No danger…the split is not violent.”

“What will happen to you?”

“Nothing, I will still be teaching English in Bratislava for $125 a month”

“Are you still sleeping the jail?”

“No…sharing an apartment in an Ex-Soviet building…only difference beween Canada

and Slovakia that I see around here is that nobody smiles much..except the students…they

smile a lot…

“Nice kids?”

“Super….How would you like to be guest teacher for a day in a Slovak High School?

“Love to, Kevine…We are coming…sounds exciting.”

“Good. I will rent a Skoda…no one will know you are tourists.”

(now that was a laugh…Marjorie wore her bright pink coat…No one else did.)

ON JANUARY 1, 1993 CZECHOSLOVAKIA SPLIT INTO TWO STATES…THE CZECH AND SLOVAK

REPUBLICS.

Czechs and Slovaks did not really want to split There were tensions between the two

groups. Many Slovaks resented the Czech dominance and general affluence. But the

resentment was not the kind that would lead to civil war. Then why did the countries split?

That was what they asked each other. The answer in simplified form is that the two political

leaders … a Czech and a Slovak.arranged the split even though it seemed to be against the

national will.

HOW DID OUR SON KEVIN BECOME AN ENGLISH TEACHER IN A SLOVAK HIGH SCHOOL?

He needed a job. Kevin had jus graduated as a Canadian high school teacher but there were

no jobs in Canada. At least he could not find a job. But I am not sure he looked very hard.

He was ready to venture into the world. Wanted to do something different. Then he heard that

the American School (an international school) was hiring teachers for the Slovak school system.

The wages were $125 a month…between $4 and $5 a day. Money was not the incentive for Kevin.

Adventure was what he wanted. Young and full of piss and vinegar as they say.

Eastern Europe was in a bit of turmoil. The Berlin Wall had been pulled down. The Soviet

Union had collapsed. Many of the Soviet Republics were looking to the West…to the United

States…for leadership. The English language was seen as the key to fitting into the new

world order.

Kevin was an English teacher. Certified. What a wonderful chance to be part of

something bigger than himself. He applied for a job…was accepted…and took off almost

immediately for the new Slovak Republic which promised him free accommodation but did not

mention the room would be in a former jail. He travelled blind along with a bunch of American

newly certified teachers.

Then in March 1993, Marjorie and I joined Kevin for a wonderful winter week in a

place we had never heard of…the brand new Slovak Republic. Kevin picked us up

in Vienna and drove us to Bratislava. We passed a large Slovak nuclear Reactor that the

Austrians felt was in danger of melt down. That put a little extra tension into the visit.

The Austrians feared this Slovak nuclear reactor was not safe. No provision for the

retention of radioactive water in a containment pool was one of the reasons…I think.

It was years later

that another Soviet reactor became world famous at a glance called Chernobbyl.

WHAT WAS LIFE LIKE IN THE NEW SLOVAK REPUBLIC?

COMPLICATED. Best answer I can put forward. Life was grim for many. Some Slovaks were happy. Some Slovaks were unhappy.

“Best not to smile when riding

the Busses, Dad. Most Slovaks are having a tough time right now. Not much to smile about. Many still believe

that Marxism could have provided a Worker’s paradise. Problems happened when Joseph Stalin and Russian communism not took

hold of Eastern Europe. “

“Seems the bullets of World War II have pock-marked some of the buildings.”

“That war …1939 to 1945 …is still part of the Slovak consciousness.”

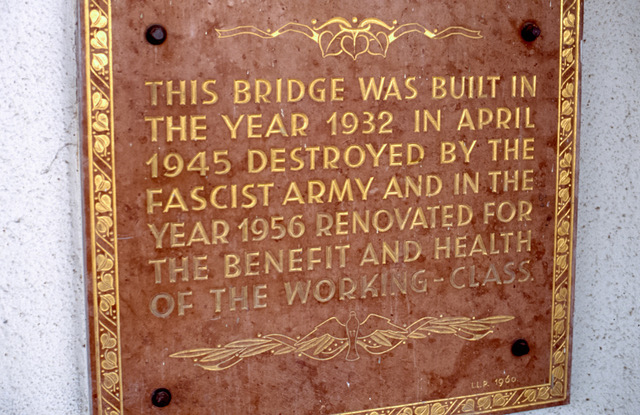

Why was this sign on this bridge in English?

We went to church on Sunday and could not help to see the huge ruin of a burned our synagogue next door to the Roman Catholic cathedral.

That was chilling. I wondered why the ghostly hulk was left standing. Perhaps a symbol of the Soviet victory of Nazi fascism. But I am

not sure why? Then there was a bridge with a memorial place engraved in English…also a reminder of World war II.

Behind this overgrown scrub forest was a burned out synagogue as seen below.

A reminder of the anti semitic terror that swept through eastern Europe in the 1940’s

TEACHING HISTORY IN A SLOVAK HIGH SCHOOL

“We have a guest today,” announced the principal as we wedged ourselves into the packed classroom.

“Welcome,” And all the students…senior students in Grade 12…all of them immediately stood

up and welcomed Marjorie and me with bug smiles. That courtesy does not happen in Canada.

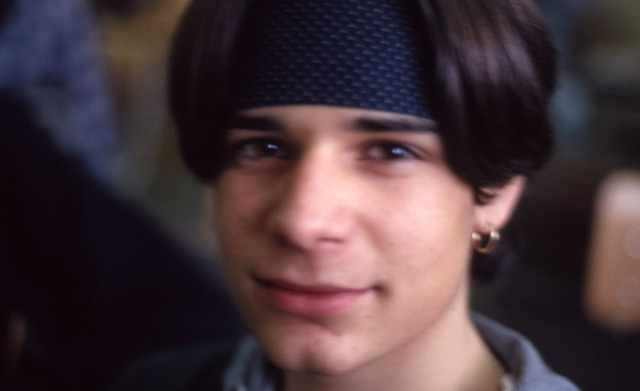

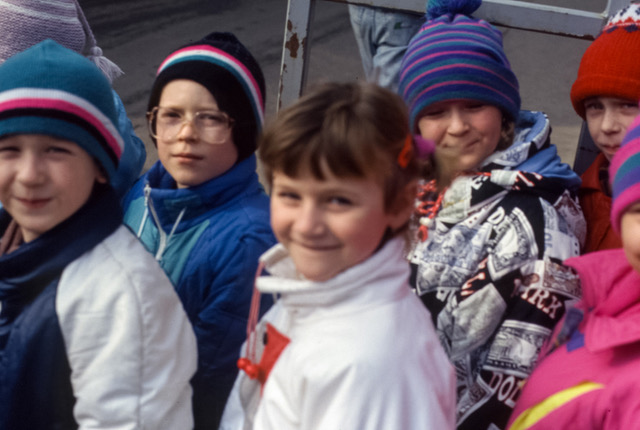

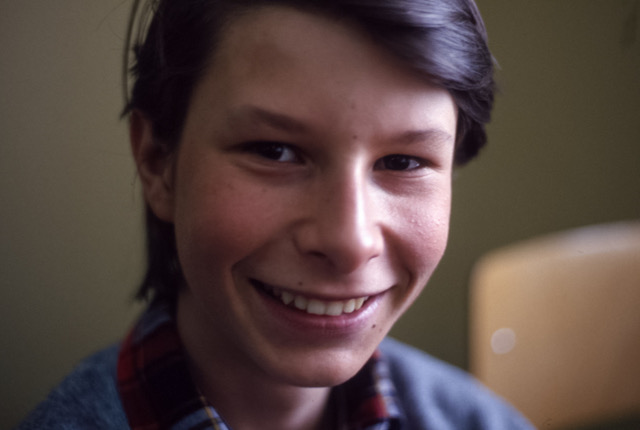

I do not remember what I taught on that cold March morning in 1993. What I do remember, however, were the

warm smiles … the joy the students seemed to feel … the hope they shared, hope that the West would change

their world. The need to speak English.

Take a look at their faces. They were 17 and 18 in 1993. Today they would be 45 and 46 with teen age children of their

own. A really nice bunch of very typical high school students whose skills in English were very good. Hopefully they can still smile the way they did in 1993.

Elementary school students

AT the back of the room, left to right, Marjorie Skeoch, VP, Kevin Skeoch, School Principal

Principal of the Slovak High School in 1993

We had quite a few adventures in our week. Perhaps the most humourous was when

Marjorie got mugged by a group of five or six older women. Likely Roma. They surrounded her outside a Slovak coffee shop

where she lined up to go to a washroom. Public WC’s were hard to find.

wile Kevin and i were paying the bill. Suddenly, Kev, yelled. “Mom is getting robbed out there.”

And sure enough the women were all around her in the line up which they used as cover. Pushing…while looking

away….distracting Marjorie while one woman slipped her hand into Marjorie’s purse and grabbed her wallet. Only it was not

her wallet. It was her glass case. The women took off as Kevin arrived hollering like a stuck pig. So the mugging turned into

an adventure where no one got hurt…and five women were sharing an empty glass case. Another group of gypsy women

encircled me at the same time so Kev used back to save me. I was in no danger…wallet tied down.

NEXT EPISODE ON SLOVAKIA WILL BE AMUSING IN PLACES…STARTLING IN OTHERS.

PRAGUE, CZECH REPUBLIC – Last Sunday marked the 100th anniversary of the foundation of Czechoslovakia… a country which ceased to exist a quarter of a century ago. Which begs the question: Why did Czechoslovakia actually break up?

On January 1, 1993, Czechoslovakia split into two independent states, the Czech Republic and Slovakia, in what is now known as the “Velvet divorce” (in a reference to the Velvet revolution) due to its peaceful and negotiated nature. Both countries divided their common “goods” (embassies, military equipment, etc.) on a two-to-one ratio to reflect their populations. Although the dissolution didn’t lead to any unrest or bloodshed, the new frontiers did create a few odd situations, like splitting border-towns in half.

The split “was not entirely inevitable, but the political and economic costs of keeping the country together would have been extremely high”, pointed out Jiri Pehe, political analyst and former advisor to Vaclav Havel.

The division of Czechoslovakia: an undemocratic decision?

A widespread narrative argues that the divorce was a purely political move decided behind closed-doors by Czech and Slovak leaders Vaclav Klaus and Vladimir Meciar against the will of the population. There is some truth in that: all the opinion polls at that time showed that a vast majority of Czechs and Slovaks was in favour of the preservation of Czechoslovakia and against the country’s break-up.

In its January 1, 1993 edition, the New York Times wrote: “A multi-ethnic nation born at the end of World War I in the glow of pan-Slavic brotherhood, Czechoslovakia survived dismemberment by the Nazis and more than four decades of Communist rule only to fall apart after just three years of democracy”.

Although no referendum was ever held on the matter, democracy was indeed at the heart of the issue: all the problems associated with the federation of two states of unequal weight and size only appeared after the centralized, communist regime collapsed as Czechoslovakia reconnected with democracy. The decision-making paralysis and the federal government’s inability to push any significant reforms in the early 1990’s strongly contributed to the top-down decision of Klaus and Meciar.

Yet, the truth is slightly more complicated. Although most Czechs and Slovaks wanted to preserve Czechoslovakia, both sides yearned for a reformed, mutually incompatible version, founded on deeply-rooted historical grievances and frustrations. And while Slovak nationalism sentiment strived for more autonomy, Czech nationalism embraced Czechoslovakism, mainly due to their privileged position within the federation.

The “arrogant” Czechs

Slovaks didn’t completely adhere to the concept of Czechoslovakism, which they often saw as a patronizing and paternalist Czech policy ever since the foundation of the First Republic in 1918. “The majority of people in Slovakia really considered Czechoslovakia as their genuine home”, Juraj Marusiak from the Slovak Academy of Sciences pointed out.

But they wanted more autonomy, more control on their own decision-making and were weary of feeling that their fate was decided by bureaucrats in Prague (the federal capital) who looked down upon the less-developed Slovak “little brothers”. “Some Slovak demands – for example the modification in the name of the country – were ridiculed by the Czech media and understood as petty of Czech politicians, who did not appreciate the symbolism of such steps for the Slovaks”, Jiri Pehe highlighted.

Despite having largely benefited from economic assistance from the Czech side during their common life, “resentment of what some Slovaks saw as a distant, arrogant federal government in Prague, was skillfully fanned by Mr. Meciar, a former Communist who saw the reviving Slovak nationalism as his ticket to power”, wrote The New York Times.

The “ungrateful” Slovaks

Czechs, on the other hand, felt like they were paying out of their own pockets for the economic and regional development of the poorer (and seemingly ungrateful) neighbor. Although Slovak GDP per capita had already reached roughly three-quarters of the Czech figure in 1992, “the animus created on the Czech side by these payments (…) was exploitable by ambitious politicians”.

First and foremost, Vaclav Klaus, a liberal economist who wanted to bring the Czech Republic at the forefront of Europe’s liberal economic transformation and needed centralized power to launch sweeping and radical reforms. This explains why Klaus was not so keen on granting more autonomy to Slovakia and appeared, therefore, more than willing to get rid of the Slovak “burden”.

Moreover, many Czechs saw as a betrayal the fact that, in 1939, Slovakia formed its own autonomous state which, despite being a puppet regime of Nazi Germany, was separate from the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, under direct Nazi occupation. On the other hand, this experience of statehood empowered part of the Slovak elite, which perceived the restoration of Czechoslovakia after the war as a “re-provincialization” of the country.

Similarly, many Czechs believed that their punishment and suffering were much greater than what the Slovak side experienced after the 1968 invasion – Gustav Husak, first secretary of the Communist party of Czechoslovakia, Czechoslovakia’s President and architect of the “normalization era”, came from Slovakia. czechoslovakia break up

The aftermath of the break-up of Czechoslovakia

After the split, both countries went their own way: “In the aftermath, M. Klaus pursued the rapid privatisations that made the Czech Republic an economic star of central Europe, but also created public resentment, as ex-communist insiders and foreign multinationals benefited disproportionately from the process”, wrote The Economist. “M. Meciar, meanwhile, tightened his grip and ruled as a semi-authoritarian strongman, slowing the progress of his country’s accession to the European Union and briefly making it a regional pariah, until he was democratically displaced in 1998”.

The demographics also significantly changed: while the Czech Republic became an ethnically homogeneous country, Slovakia was still home to a strong Hungarian minority (nearly 600.000) and Roma community (between 300.000 and 500.000).

The “Velvet divorce” has often been conjured to tackle contemporary separatist movements throughout Europe (Catalonia, Scotland, Brexit, etc.). “Policymakers wondering how a euro zone disintegration would play out could do worse than study one monetary union collapse that went well: the split of the Czech-Slovak currency union” in February 1993, even wrote Reuters. czechoslovakia break up

Czech Republic and Slovakia go their separate ways: what’s the situation today?

Despite their break-up, the Czech Republic and Slovakia remain more closely linked than any other two countries in Europe. Although the dissolution was experienced as a defeat and a failure for many people, no one is seriously pleading for reunification. We should also point out that Czechs and Slovaks were separated throughout most of their history: their Czechoslovak “joint-venture” appears more as an exception than the rule. Even within the Habsburg Empire, Czechs were under the rule of Vienna, while Slovaks were governed from Hungary.

Their relationship to their common past remains highly asymmetrical and strained by long-running prejudices on both sides. While the aforementioned grievances have something to do with it, more current grievances (like the fact that the Czech Republic cunningly stole Czechoslovakia’s flag after the break-up) also play a role in the enduring stigmas on each side of the border.

Last week-end’s celebrations proved it well. While the Czech Republic celebrated the centenary of the foundation of Czechoslovakia in style and with great pomp, no event of such magnitude was held in Slovakia. October 28 is one of the major Czech public holidays to celebrate the independence and statehood… of a country that no longer exists.

In Slovakia, it’s only qualified as a “memorial day”. However, to mark the centenary, the country instead decided to implement a one-off public holiday on October 30 this year. January 1, meanwhile, despite being the official “independence” day for both states, fails to have any real significance today: partly because neither Slovakia nor the Czech Republic want to “celebrate” the 1993 dissolution, and partly because it’s overshadowed by New Year’s Day.