Loading

|

|

A Rock Fell on the Moon Gerald H. Priest: His life and crime against a ‘company of fools’ By Jane Gaffin

It was a masterfully-crafted madcap scheme against what was once one of the richest silver camps in the world. The architects were two highly-intelligent co-conspirators who proved, however, there is honour among thieves. Gerald Henry Priest, along with Anthony “Poncho” Bobcik, a big, jovial Czech, refused to tattle on a third party, a mine captain, believed instrumental in pulling off the ruse but his deeds went unproven. Adding to the further frustration of baffled police investigators, United Keno Hill Mines (UKHM) workers remained mum on all counts, too. In solidarity, they refused to squeal on one of their own. The 671 twill sacks full of high-grade ore were supposedly hand-mined legally by the two men from their Moon mineral claims and salted with a few allowable precipitates rejected from the mill. If, on the other hand, the pair actually committed criminal sin, then the workers’ admiration escalated a thousandfold in a “good for them” attitude. A large percentage of workers held a direct contempt for the mining company and maybe an indirect disdain for the Toronto-based, multi-national parent corporation, Falconbridge Nickel Ltd. Much of this scorn would not have metastasized into such hostility except for the dictatorial UKHM general manager whose ghastly managerial practices were unprecedented. He didn’t seem to like the company he managed and definitely wasn’t a people-person. Maybe, as an inept manger, he should have been held indirectly responsible for causing the ruckus and did eventually receive his comeuppance in something akin to a storybook theme of “good trumps evil”. Until Harbour Publishing released daughter Alicia Priest’s book A Rock Fell on the Moon: Dad and the Great Yukon Silver Ore Heist (peek inside at Kindle’s sample chapters) on the 2014 Christmas list, nobody except family members and maybe a few close friends had an insight into what made Gerald Henry Priest tick. Some people viewed United Keno Hill Mines’ chief assayer as a friend; others saw him as moody and mercurial; Judge John Parker, responsible for sentencing, noted Priest to be “a strange bird” and condemned him for harbouring a grudge against society. None got it quite right. Priest had it all. Yet like Robert Service’s poem “The Men Who Don’t Fit In“, which suits Priest to a T, he sadly wouldn’t admit his mistakes until he was robbed by that sneaky devil called time. His self-analysis came too late to pick up the fractured pieces and make amends. He was a clever man. He had a flair for writing, could remember lyrics to tunes, accompanying himself on a guitar, and recite Robert Service poems by heart, the reason the author has opened each of 20 chapters plus the epilogue with appropriate lines lifted from a variety of the bard’s verses. He was a great storyteller, spinning wild fables into plausible tales that turned skeptics into believers. He and his geologist cronies convinced a court in Round One that “in geology, anything is possible”. How could six jurors, who wouldn’t have known a sulphide from the city limits, counter the experts? Maybe a rock really did fall on his Moon mining claims millions of years ago, and Priest simply took advantage of mining Mother Nature’s gift. As the story unfolds, the reader constantly vacillates between his guilt or innocence. Priest and his family lived in a company-owned Panabode house, reserved for Elsa’s upper echelon. Inside, the comfortable, cozy, varnished, log-style home was rich with music, books, a cat and much-loved Belgian shepherd, Caesar. His home was his castle where he didn’t have to exert effort to boil a kettle or wash a sock. He had a well-paying job, a beautiful, affectionate wife; and two daughters, Vona and Alicia, born 360 days apart, who revered him as only little girls can. Or, as the author inquires, did he perhaps see things differently? “Four female dependents, an ailing wife [heart problems] who couldn’t give him the son he deserved; a religiously fanatical mother-in-law, a tedious dead-end job for a company of fools and two daughters who revered him as only little girls can?” Gerald Preist changed. Dramatically and sadly. But he never completely let go of the his claim that a huge lump of silver fell on his Moon mining claims.

His family were affected disastricsllly. When Gerald was suspected of stealing high grade

silver ore from the United Keno Hill mine based in Elsa, he was fired. Hisfamily found

a new home in a small basement apartment in Vancouver. Their life never got back on

the rails.

HELEN PREIST

Helen’s mother, Maria, was a survor of the mass migration of German civilians racing on foot to get

to the West before being enveloped by the Red Army as it advanced relentlessly in1944 and 1945.

Helen Preist is much more difficult to present. Gerald Preist was easy. His early life and married life was qite ordinary which makes the change he underwent quite striking. Helen, however, hd an extraordinary and

very terrifying life before she married Gerald. Helen and her mother Maria (Omi) were part of the German frantic

race to get to the Western border at the end of Work War II. They were German Mennonites whose ancestors had been

encouraged to migrate to the rich black soils of the Ukraine. Pacifists. People of the book. Believers that this life

was only s trial before the life after death. Farmers. Skilled craftsman. People who did not intermiz=x much with

the existing Ukrainian people.

Most people would want to keep their family skeletons stuffed permanently inside a locked closet, not to be whispered about ever. This memoir cum thriller doesn’t masquerade the warts and blemishes but uninhibitedly rattles the bones in an effort to dig out the truth. It was way past time for half-truths and speculations written by others to be set aside and for the author to tackle the prickly job of fully disclosing her father’s good points, which is why she loved him, as well as his misdeeds, for which she couldn’t forgive him. His frank, candid, resilient, loving daughter, Alicia, was the only person who could pull off the thorny assignment properly, coupled with invaluable assistance from her own “rock”, husband Ben Parfitt, a writer in his own rights. As though Papa’s story doesn’t provide enough surprises when turning every corner, the reader is bolted over with an unexpected double dose of intense family history from the maternal side of the equation. As a girl, Maria, or Omi as her loving granddaughters addressed her, had fallen from riches to rags, having begun life in a wealthy, Russian land-owning family who lost everything, including themselves, to revolution and anarchy. With her birth family and her only living son, Peter, imprisoned somewhere in the Gulag, she suffered a lifelong survivor complex. While guilt was somewhat assuaged by strong Mennonite convictions, in her mind she was a sinner. “In the terror time, I did what I did to stay alive,” she was quoted as saying. God only knows what sins she committed to survive and it’s best not to probe. Many Ukrainians refrained from discussing this awful past, although some did loosen their aging tongues so the next generation would have an inkling about Holodomor. Josef Stalin’s man-made famine exterminated unknown millions through deliberate starvation in the 1930s. When the Soviet’s army confiscated the crops, not leaving a grain, much less a percentage of the harvest for the villagers’ winter food supply, residents resorted to eating cats, dogs, exhumed horses, leaves from trees, then each other. Survivors were fortunate if they came through the terror with their memories blocked and sanity in tact. An excerpt from a eulogy Alicia wrote in the Globe and Mail when her mother, who survived two husbands, died in 2011 hints at Helen’s tough-fiber: “If life is an obstacle course, Helen Young was a gazelle. Spirited, elegant and beautiful, she had a fragility and charm that masked her determination to clear one hurdle after another.” Lolya, or Helen, was born November 24, 1924, in what was at the time southern Russia and is now the Ukraine. She was the second child and only daughter of Maria Reger and Abraham Friesen. Her younger brother Alexander died of diphtheria at 18 months. Her family moved away from their large extended Mennonite clan in the Ukraine to Ebental, a small village in the foothills of the Caucasus Mountains, As a Mennonite, her mother tongue and heritage were German, the enemy of Stalin’s USSR, where their religious freedom was no longer tolerated. In 1930, Helen’s mother, Maria, learned that her parents, sisters and brothers had been loaded in cattle cars and shipped to Siberia, two children dying along the way. The Soviet regime became their immediate enemy. Under a psychopathic Stalin, the Caucasus region was no safer than the Ukraine had been. Three years later, Helen’s father collapsed and died at age 35, having learned his name was on Stalin’s personal list of who would live or die after rounded up and brought before his secret police for interrogation. Within two years, Helen’s mother married another Mennonite, Heinrich Werle, a university-trained agronomist responsible for ensuring the late August harvest of the area’s wheat crop. The “progressive” state forbade the use of horses which were “replaced” with non-existent combines. Caught in a life-and-death conundrum, Werle ordered farmers to hitch up the horses and bring in the harvest. The act was truly part of the Harvest of Sorrow. The crop secured, Werle was banished to a northeastern hard labour camp. In 1940, Helen, of high school age, and her mother, Maria, moved to still a larger town, Stepnoye. Helen’s older brother Peter, now 17, had stayed behind in Ebental to care for the family’s small house and few animals. The following year, he too was arrested and instantly disappeared to the Gulag, along with other relatives who were assumed to have all perished in that inhumane, Stalin-devised hellhole. In 1941, the Nazis marched into the Caucasus. Due to their common language and common hatred, Maria saw them as liberators. When the Russian army launched its massive counter offensives in the winter of 1943-44, Helen and Maria were forced to escape by foot, horse-drawn cart and cattle car along with the Germans. Nineteen-year-old Helen and her mother arrived in German-occupied Poland, ultimately making their way to Germany where they were greeted with mass terror as buildings were reduced to rubble by Allied bombs. Helen secured a respected job as a Russian-German translator for Kommission 28, a division of the German Reich. In the fall of 1948, a Canadian Mennonite family put up $500 to sponsor the hard-working mother-daughter duo to resettle in Matsqui, British Columbia, where Abraham and Helene Rempel, who remained life-long friends, gave them a home and a community. After paying off their ship and train fares labouring in the fields, they were free to venture out on their own. After crossing two continents and the Atlantic Ocean, Helen felt rejuvenated. What better way to cement her new self to her new nation where she finally felt safe than to marry a real Canadian? Before marrying Gerald Priest, she had turned down a United Nations collection of suitors: a Russian, Pole, Italian, three Germans and an American as well as a dedicated Mennonite whose plans to work overseas as a missionary was not for her. Neither was the Yukon’s jerkwater mining town of Elsa, where she sparkled like a jewel in a junkheap. “A cardinal in a town of sparrows”, as the author describes her exotic mother who loved the city life that suffocated her bush-minded husband. She stitched her own chic wardrobe with help from a nimble-fingered mother and dressed the two girls in matching ensembles. She never owned a pair of jeans in this mining town of boardwalks, bladed lanes and unpaved roads, covered in either snow, ice, mud, dust, dirt or gravel, depending on the season. I didn’t want A Rock Fell on the Moon to end. The writing style is crisp, fast-flowing, and humourous, the sentences often loaded with fresh, witty similes and metaphors. With pages nearly exhausted, I didn’t believe space remained to run headlong into any more jolting surprises around the next corner. While only a fool tries to out-judge a judge, the reader should never try to outguess how Alicia Priest would choose to present her true “whodunit”. At this point, Gerald Priest didn’t have two plugged silver pesos to jangle together in his jean pocket. But he had chutzpah. His blood boiled every time he thought about American Smelting and Refining Company (ASARCO) in Helena, Montana, smelting his shipment of ore and sending the fat cheque for $125,322.17 to United Keno Hill Mines before the courts had determined who owned the ore and where the ore had originated. This irrepressible guy took another jab at justice. His family, unravelling at the seams, was oblivious to his international escapades in which he convinced his new Stateside lawyer to take his civil case on contingency. Priest provided a plausible explanation to Nelson Christensen, a young lawyer working for a large, prestigious Seattle firm. He had delivered a shipment of raw ore to ASARCO in June, 1963, he explained, then two years later he had been convicted of theft. Since the worth of the ore skyrocketed in Priest’s mind with each retelling, he pegged the value of ore this time at $200,000. Long before he had been found guilty, he said, the smelter processed the disputed ore and cut UKHM a big cheque. “That’s violation of the contract I had with ASARCO, isn’t it?” Priest asked of Christensen. “It was an audacious gambit but one that Dad’s new lawyer in Seattle felt was worth pursuing,” writes the author. In 1967, notice was served on ASARCO that Gerald H. Priest was suing the smelter for breach of contract. Seattle lawyer Christensen argued that the smelter had breached the terms of the contract prior to Priest’s criminal conviction by smelting the ore before Canadian courts issued any ruling. The filing of the claim against ASARCO set off a nuclear explosion at UKHM. Before ASARCO had paid UKHM, the smelter had required the company to agree that if Priest and/or his partner, Anthony Bobcik, or Bobcik’s company, Alpine Gold and Silver, or anybody else came out of the woodwork to recover funds from the smelter, UKHM would have to reimburse the smelter. That problem was between the mining company and the smelter and had nothing to do with Priest, who sat back smirking. Revenge is sweet, even when served up cold. If Priest earned nothing else from his current gamble for a cash settlement, he at least had the satisfaction of watching the Big Boys squirming. This surprise aftermath that the author unloads at the eleventh hour is a long-obscured segment in the saga of the Moon claims. And, despite what Priest did, the reader wants to applaud this scenario that holds a bit of ironic twist against the Goliathan companies UKHM, ASARCO as well as the judiciary in Canada, who, as political bedfellows, had been beating up on a poor little David. In fact, earlier in chronological events, the Yukon judiciary’s face turned red with rage — or more to the point, Judge Parker’s — due to a couple of other overlooked glitches: “It’s not what you know, but who you know” that counts and “Never underestimate the power of a woman” who just might be working on the “outside” in favour of securing the release of her husband who’s been helplessly incarcerated like a fly in a jar on the “inside”. The author’s interesting website can be visited at www.aliciapriest.com where more can be learned about this courageous woman’s date with her “ultimate deadline”, ALS, better known as Lou Gehrig’s disease. Jane Gaffin is a freelance writing living in Whitehorse, Yukon, Canada and can be contacted at janegaffin@northwestel.net or visited at www.janegaffin.wordpress.com. Buy A Rock Fell on the Moon at Amazon.com for only $23.62 |

Priest heist remains a conundrum

A Rock Fell on the Moon: Dad and the Great Yukon Silver Ore Heist (Lost Moose $32.95) by Alicia Priest is a poignant family story that reveals a little-known vein of silver mining history beyond yarns of Klondike gold.

August 20th, 2014

bcbooklook.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/ARockFellOnTheMoon_HelenWithHerTwoDaughters_Image1-1024×686.jpg 1024w, bcbooklook.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/ARockFellOnTheMoon_HelenWithHerTwoDaughters_Image1-188×126.jpg 188w, bcbooklook.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/ARockFellOnTheMoon_HelenWithHerTwoDaughters_Image1.jpg 1400w” sizes=”(max-width: 300px) 100vw, 300px” style=”border: 0px; font-family: inherit; font-style: inherit; margin: 0px; outline: 0px; padding: 0px; vertical-align: baseline; max-width: 100%; height: auto; width: auto;”>

bcbooklook.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/ARockFellOnTheMoon_HelenWithHerTwoDaughters_Image1-1024×686.jpg 1024w, bcbooklook.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/ARockFellOnTheMoon_HelenWithHerTwoDaughters_Image1-188×126.jpg 188w, bcbooklook.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/ARockFellOnTheMoon_HelenWithHerTwoDaughters_Image1.jpg 1400w” sizes=”(max-width: 300px) 100vw, 300px” style=”border: 0px; font-family: inherit; font-style: inherit; margin: 0px; outline: 0px; padding: 0px; vertical-align: baseline; max-width: 100%; height: auto; width: auto;”>

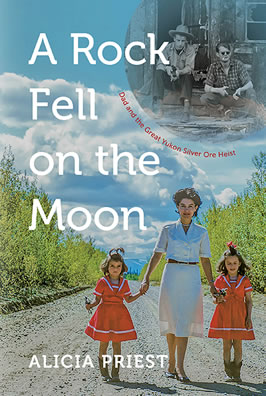

Helen Priest in the Yukon with her daughters Vona and Alilcia, prior to the robbery.

It’s also a ripping good read, patient according to Caroline Woodward, ailment who has reviewed the fascinating story of Gerald Priest—one of two alleged thieves charged with the biggest theft of silver ore in Canadian history.

—

By Caroline Woodward

Alicia Priest can still recall being uprooted from a comfortable and loving home in the remote mining village of Elsa, three hundred miles north of Whitehorse, as a bewildered ten-year-old.

Suddenly she was living with her mother, grandmother, sister and one dog in a dank East Vancouver basement suite. On her first day in the big city elementary school, Alicia Priest was asked by another grade five student if her father was the “Yukon guy in the news.”

Well, yes, Gerald Priest was one of two alleged thieves who were charged with the biggest theft of silver ore in Canadian history. But the bright little girl knew just enough about her mother’s silence and father’s absence to lie about her Dad’s identity on that day.

It has taken Priest almost a lifetime to uncover the truth. Her A Rock Fell On The Moon: Dad and the Great Yukon Silver Ore Heist offers two versions of an almost-perfect crime, and a compelling analysis of her family at the centre of the mystery.

Priest tackles the full range of facts about a daring 1963 heist, including two subsequent trials making newspaper headlines across Canada, while also uncovering difficult home truths.

Gerald Priest, the Chief Assayer (senior chemist) for United Keno Hill Mine, third richest producer of silver in the world, never publicly admitted to his role in the theft of 671 bags of ore that were 80% silver. Estimates vary radically as to its value, but it’s likely more than $2 million in today’s currency.

Did it come from piles of ore left temporarily, for tax reasons, in an unused mine tunnel? Or did the unusually rich silver come from a giant boulder found on the claims Gerald Priest staked on barren ground known as the moon, hence the wonderfully apt title of the book?

While he lived, Gerald Priest didn’t disclose anything to his daughter except increasingly far-fetched stories. She has subsequently applied her journalistic research and interviewing skills to hundreds of letters, newspaper stories, RCMP files and investigators, court documents, the Yukon Archives, lawyers, geologists and former mine employees.

Alicia Priest began her investigation in 2011, after both parents had died, not an uncommon practice for authors who must outflank and outlast any confrontation with guilty parties, accusations of hanging out dirty laundry for profit or, when dealing with the innocent and wronged, to kindly spare the feelings of these most powerful of censors. Then, in 2012, Priest was diagnosed with ALS (Lou Gehrig’s disease). This terminal diagnosis added new urgency to the task at hand, as it would do to any writer contemplating a memoir or novel.

“I received the ultimate deadline… a mother of a terminal illness,” says Priest in an interview. “I had to start there and then while I could still talk, type, eat and walk somewhat normally. With tremendous organizational help from my husband, [journalist] Ben Parfitt, I wrote and rewrote and then rewrote again for fourteen months.”

Heart-breaking, hilarious and suspenseful, hers is an impressive achievement—alternately unearthing an audacious mining mystery, taking us down into the mine itself, to the dark psychological twists and turns within her family and describing life in the mining village of Elsa, and evoking Priest’s ten years of perfect childhood.

Gerald Priest was a baffling man—funny, affectionate, well-read, at home in the bush and at the boardroom table, but also petty, devious and cruel. He preferred children—and men and women for that matter—who laughed at all his jokes and didn’t question his decisions.

Helen Friesen was a Mennonite Russian refugee from Stalinist purges and Nazi aggression. After finding passage for herself and her mother to Canada, she became engaged to Gerald Priest after a two week courtship, prefaced by several months of pen-pal correspondence, sight unseen. (She kept every single telegram and letter he ever wrote her, nearly 300 of them, while he tore up or burned nearly all of hers.)

This lively, fashionable young woman from the relatively bright lights of Vancouver, circa 1951, only made the move to Elsa, Yukon, population approximately 600 souls, after Gerald agreed to a package deal. Helen’s mother had to come along, too.

Each chapter of the book is prefaced by a quote from Robert Service. Amongst the Yukon Bard’s doggerel verse are zinger nuggets of philosophy and psychology.

“Perhaps I am stark crazy, but there’s none of you too sane; it’s just a little matter of degree.”

It’s easy to imagine the bespectacled boy who would mastermind the great Yukon silver heist reading all Jack London’s adventure novels and memorizing lines of Service’s poetry. But chance rolled snake eyes on a Friday morning in June, 1963.

Problems arose only after the driver of the flatbed truck that was loaded with bags of purloined ore took a wrong turn and had to ask for directions He parked outside the Elsa Cookhouse (barber shop, beer parlour and library) and bought cigarettes and coffee, asking how to reach the main road south.

Unfortunately the mine manager happened to look out his window and see the truck. Fridays weren’t ore-moving days… and, hey, it was a Friday!

What followed were the most expensive trials ever held in the Yukon. The legal elements include a mysterious Third Man who was never charged, or ratted out by the two men who were; the no-longer legal burden of reverse onus (meaning the men charged were guilty until they could prove otherwise); and the intervention of lawyer Angelo Branca who bowed out from representing Gerald Priest after being appointed a Supreme Court judge, an untimely honour which likely sealed Priest’s fate.

This is a consummately well-written book, achieving the near-impossible feat of maintaining a journalist’s objective distance while literally tracking her father’s fifty-year-old footsteps and disclosing painful family secrets with restraint and dignity.

978-1-55017-672-8

Caroline Woodward is the author of Penny Loves Wade, Wade Loves Penny (Oolichan 2010), a novel set in the Peace River.

Picking up the pieces of Yukon’s great silver heist of 1963

A rock fell on the moon. That’s how Gerald H. Priest explained away the 70 tonnes of silver ore that he was accused of stealing from United Keno Hill Mines in 1963.

A rock fell on the moon. That’s how Gerald H. Priest explained away the 70 tonnes of silver ore that he was accused of stealing from United Keno Hill Mines in 1963.

Gerry worked as the mine’s chief assayer at the time, and lived with his young family in the nearby company town of Elsa.

In Gerry’s telling, he had hand-picked the ore from the nearby Moon claims, which he had bought the year before.

But the rich ore matched nothing in the immediate area where Gerry claimed to have found it. Those high concentrations of silver match much more closely with finds from the mine’s Bonanza Stope, where ore measured on average 1,500 ounces of silver per tonne.

A very large boulder of rich ore could have, in the distant past, rolled down the mountain and landed on the Moon claims, resting there as surface ore, or “float,” reasoned Gerry.

It seemed as implausible an explanation to some, familiar with the area, than if he had claimed to have found the ore on the moon itself.

But Gerry’s confident and self-assured nature left the FBI agent who interviewed him in Montana with the impression that he was a man with nothing to hide.

And the Whitehorse jury who first heard Gerry’s case was left deciphering conflicting expert testimony about whether or not that rock could have landed on the Moon.

One geologist gave three theories on how that ore could have ended up where Gerry said he found it. It left the court with the impression that “in geology, anything is possible,” according to one of the investigators.

The longest, most expensive and most complex trial to that point in Yukon history ended with a hung jury, although Gerry went on to be convicted of the crime in a second trial, and ultimately did time in one of B.C.‘s roughest penitentiaries.

The story of Yukon’s great silver heist of 1963 had previously been recorded only in scattered accounts in a handful of history books, and in piecemeal records mostly lost to the basements of RCMP and courtroom storage rooms.

Now Alicia Priest, who knew Gerry as “Pappy,” ties the threads together in her newly-released book, A Rock Fell on the Moon: Dad and the Great Yukon Silver Ore Heist.

The book is partly a memoir of an idyllic Yukon childhood in the bygone era of the mining town, ripped apart at the seams by a father’s dreams of fortune.

It is also a true-crime story, telling a piece of Yukon history that could have been slowly lost along with the memories of those who lived through it.

Finally, it is an account of Alicia’s effort to piece together her own history, visit the places of her childhood and learn something of the man her endlessly adored father had been.

Alicia’s effort to tell her family’s story was indeed extraordinary. She was diagnosed with a degenerative and terminal neurological disorder, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), in 2012 and only starting writing the book after that.

“That’s when I received the ultimate deadline,” she says in the press kit for the book.

“If I was going to write the book, I had to start there and then while I could still talk, type, eat and walk somewhat normally.”

She finished the manuscript late last year.

“It was a long time coming, because it was becoming harder for her to write,” says her husband, Ben Parfitt, who is also a journalist.

“She has a lot more determination than I gave her credit for. I really felt at times that it was going to be too much for her to do what she did.

“I’m thrilled and she is thrilled beyond words that she was able to finish the manuscript.”

Ben and Alicia will be in Whitehorse next week to officially launch the book.

Alicia has been back to the Yukon a couple of times, and Ben has visited, too, but they have never come together. They plan to visit Atlin, B.C., for a night, if weather permits, a spot they both know and love.

“It’s a special trip for us,” says Ben.

What really happened on those evenings when Gerry Priest left the comforts of home and family and disappeared into the dark, frigid Elsa night?

Sometime in July 1961, two underground miners start to work under cover of night to squirrel away portions of the richest vein of silver ore in the mine’s history in abandoned tunnels.

In August one of them, nicknamed “Poncho,” is hired in the assay office where Gerry is boss.

In March, the mine announces that a previously deactivated section of the mine will be recommissioned. That’s when Gerry’s nighttime disappearances begin.

Later that year, he buys the remote Moon claims, and registers a company in his name.

And on June 21, 1963, three truckloads loaded with ore head out from Keno destined for a smelter in Montana.

The shipment may have escaped undetected if one of the driver’s had not gotten turned around and stopped for directions at the Elsa Cookhouse. It was spotted there by the mine’s general manager, who ordered samples of ore stolen from the truck.

Gerry admitted his role in the heist to his wife and later to Alicia’s sister, Vona, but never to Alicia.

“For years, I didn’t know the full story,” writes Alicia in the press kit.

“I believed he was innocent and wrongly convicted, and his subsequent humiliation was just too much to bear.”

In the book Alicia paints the portrait of a man so stuck in his stubborn pride that he can barely admit to himself his own lies.

Guilt and incarceration brought out her father’s worst traits, Alicia writes. “Bitter, cynical and emotionally twisted in some weird way.”

The family fell apart for good in 1969, and for more than two decades of her adult life Alicia was mostly estranged from her father, although she says she never stopped loving him.

He died at a nursing home in 2006, “toothless, penniless, diapered and demented,” the day after Alicia saw him for the last time.

She vowed then to “some day soon” delve into the true story, she writes.

“He broke our hearts. It took me decades to get over it”

But left among the wreckage Alicia found a story worth telling.

She hopes above all that readers find the book to be a pleasurable read, she writes.

“Also, I hope readers gain a glimpse of a lost world, an overlooked snippet of Canadian history, and perhaps a wee lesson about taking care who you marry.”

The launch for A Rock Fell on the Moon will take place Wednesday, October 8 at 6 p.m. at Baked Cafe in Whitehorse.

Contact Jacqueline Ronson at

An ingeniously-plotted high-grade silver ore heist in the Yukon Territory has intrigued mining people, crime aficionados, lawyers, investigators, writers and others since a lengthy 1963 trial was staged in that northern, backwater, federally-controlled jurisdiction that most Canadians still can’t find on a map — a place the author of A Rock Fell on the Moon assesses as having milked the 1898 Klondike Gold Rush history “like a menopausal cow”.

An ingeniously-plotted high-grade silver ore heist in the Yukon Territory has intrigued mining people, crime aficionados, lawyers, investigators, writers and others since a lengthy 1963 trial was staged in that northern, backwater, federally-controlled jurisdiction that most Canadians still can’t find on a map — a place the author of A Rock Fell on the Moon assesses as having milked the 1898 Klondike Gold Rush history “like a menopausal cow”.