Trophies across Canada

At war’s end, Sir Arthur Doughty, the Dominion Archivist, was named Controller of War Trophies and charged with gathering trophies and bringing them back to Canada. While many Canadian trophies were sent to the Imperial War Museum, thousands returned to Ottawa. In early 1920, the government’s official collection consisted of 516 guns, 304 trench mortars, 3,500 light and heavy machine-guns, and 44 aircraft.

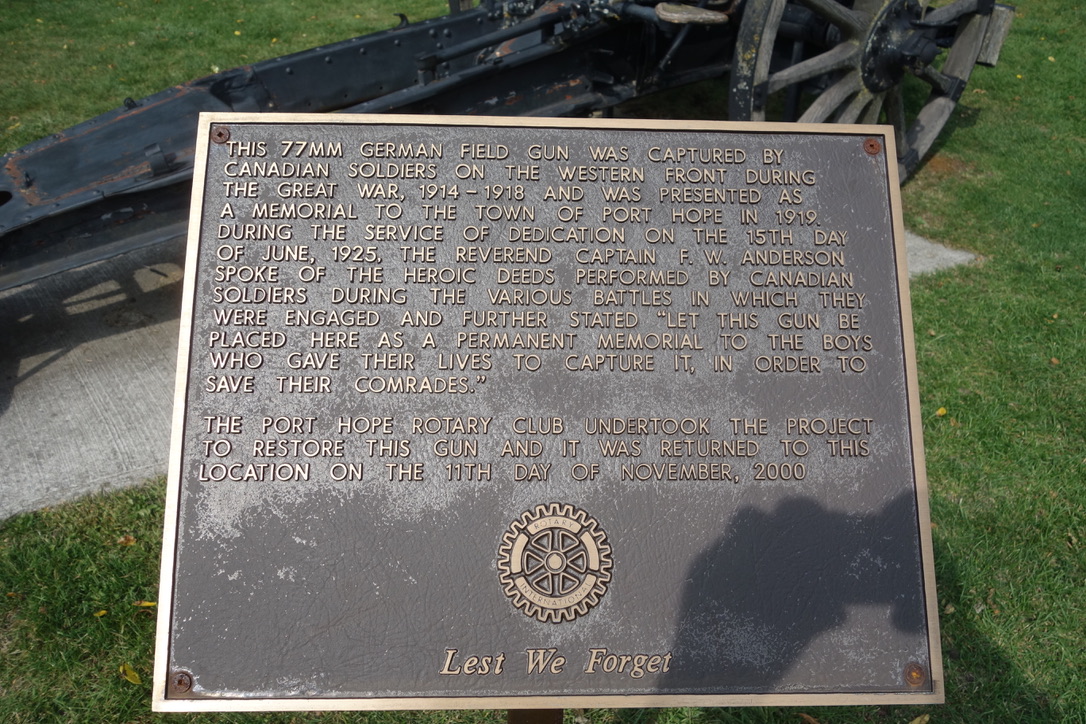

Initial plans for a national war museum to house this collection, the official war art, and other artifacts were delayed or ignored by successive governments. The collection remained with the Dominion Archives which was soon sending pieces of it across Canada in response to requests from communities, veterans groups, schools, and military units. Cities or military bases often displayed large war trophies in central parks or in or near prominent buildings, and sometimes included them with local memorials. Acquired in the burst of patriotic enthusiasm that marked the immediate post-war period, many gradually fell into disrepair. During the Second World War, hundreds were donated to scrap metal drives, incorporating former German weapons against the new Nazi enemy.

What happened to them? Initially they were stored in Ottawa but not for long. Towns and cities across Canada sent requests for war trophies…as did veterans group, schools and military units.

Many got featured space in parks or near prominent buildings as in Port Hope. If there were so many then why did the Port Hope gun surprise me?

The fate of the larger trophies of war…the airplanes is only partially known. Believe it or not Germany surrendered 792 Fokker Aircraf

QUOTE FROM :THE CANADIAN FOKKERS

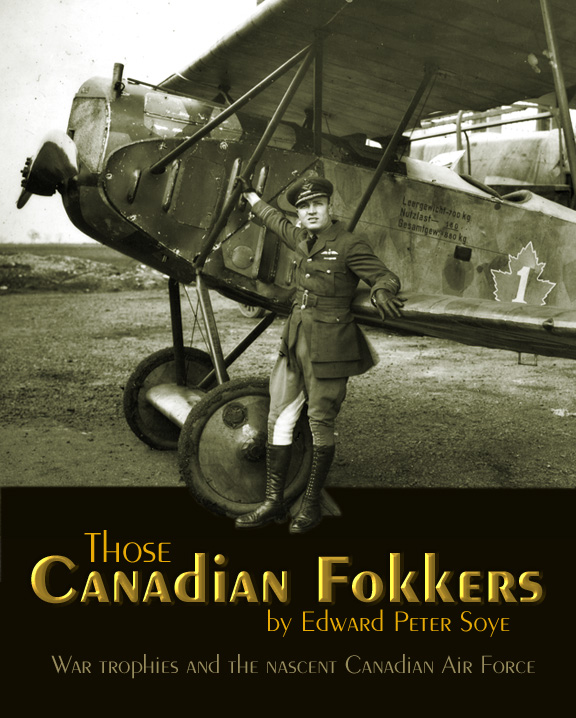

By the end of the Great War, military aviation had come of age and was recognized as a vital part of modern warfare. The Armistice of November 11th 1918 required the German Army to surrender its most potent weapons of war, so as to discourage the high command from resuming hostilities. This agreement demanded the German army turn over 5,000 artillery pieces, 25,000 machine guns, 3,000 trench mortars, as well as “1,700 pursuit and bombardment airplanes, preference being given to all of the D-7s [sic] and all of the night bombardment machines”. As a result, by the opening months of 1919, 792 Fokker D.VIIs had been surrendered to the British, French, Belgian and American armies. Several dozen of these machines ultimately found their way to Canada, and yet the details of exactly how that happened have been all but forgotten.

From a Canadian perspective, the First World War was a pivotal moment in terms of establishing a sense of nationhood. Thousands of Canadians fought with distinction in the British flying services during the war. On the ground, the Dominion of Canada fielded its first Army-sized formation – the four, over-gunned divisions of the Canadian Corps. To publicize this significant contribution to the allied war effort, Lord Beaverbrook created a public relations machine called the Canadian War Records Office (CWRO). Working with him to construct and preserve a national memory of the war years was Arthur Doughty, Dominion Archivist and Director of War Trophies. Drawing largely on spoils of war surrendered after the Armistice, Doughty amassed an artefact collection including nearly fifty aircraft. Along with the rest of the trophy collection, these state of the art aeroplanes were intended to form the nucleus of a national war museum in Ottawa to commemorate Canada’s wartime sacrifices.

During the opening months of 1919, Doughty and a young Canadian staff officer by the name of Captain R.E. Lloyd Lott persuaded the RAF and the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) to share a portion of their aeronautical booty with Canada. In February and March of 1919, the recently formed Canadian Air Force (CAF) took possession of twenty Fokker D.VIIs from the RAF. The original intent was for the CAF to pack the aircraft for shipment to Canada, but No. 1 Fighter Squadron also flew them extensively alongside their standard British service machines. In part, this was because the experienced Canadian airmen felt that the D.VII was superior to their issued Sopwith Dolphins.

Today, assessing the degree to which the CAF utilized German aircraft is based on a number of primary sources. Among the most useful documentary evidence is a handful of surviving pilot logbooks. In addition to these, a number of official Canadian photographs – one of the many products of Beaverbrook’s CWRO – captured Fokker D.VIIs in CAF custody. In the spring of 1919, CWRO cameramen visited the CAF at Hounslow Airfield (southwest of London, between the modern Heathrow Airport and Kew Gardens) where they photographed Fokkers D.VIIs being used by Canadian airmen. A number of these photographs have since been published fairly widely, yet their Canadian connection is most often entirely overlooked.

The photograph showing a line-up of four Fokker D.VIIs (the nearest bearing the ‘RK’ insignia of Richard Kraut from Jasta 63) has appeared in a number of publications. Some rightly identify the location as Hounslow, but never has a caption indentified the serials of all four aircraft in the photograph, nor has anyone noted that they were being utilized by the CAF. Through an examination of original CWRO albums held at the Canadian War Museum (CWM), and an appreciation of context in which the photos were taken this author has deduced much information about the images in this series. Two other photographs of this same foursome, taken from different angles and showing a handful of CAF members, allow the four aircraft to be identified as Albatros-built D.VIIs bearing the serials 5924/18 [often misidentified as 5324], 6769/18, 6810/18 [the so-called ‘Knowlton Fokker’ that survives in Canada to this day at the Brome County Historical Society] and 6822/18. In order to extract this information, one requires access to all three photographs, an appreciation of their relationship to one another, and good quality scans or prints from the original glass plate negatives.

ALAN SKEOCH