Page 2

NOTE: I have begun to transcribe this story which was originally

written in an attempt to discover how RCAF sergeant George Freeman

died on May 27,1944…as time permits I will transcribe the story…and look for the pictures.

There will be typos.

THE LAST FLIGHT OF HX 313

(Original written in 1984, Current rewrite Oct. 2019)

alan skeoch

Death doesn’t impact on a six year old as much as it does on an adult. When George Freeman was declared missing on May 28, 1944, I barely noticed.

My parents were a little different that day I imagine. Quieter. Distracted. My brother Eric and I may have slipped out to Dufferin Park as usual. We didn’t

really know there was a war being fought in Western Europe, the Middle East, Burma, China and islands chains of the Pacific Ocean. Not real to us at all

To us the world war was fantasy as we spent a lot of time playing ‘guns’ with wooden weapons made from cast offs from the local piano factory. We spent

more time playing cowboys and indians than replicating the confusing combatants of World War II.

The only real war we knew about were the gang wars between the Beanery and Junction gangs which seemed to rage regularly when waves teen age hoodlums

attacked each other with lead pipes and baseball bats or fists and hand held broken beer bottles. Time has magnified these fights in my memory. There are

only a few news clippings that even mention these battles. Eric and I did see some battles that’s for sure. As to how often I cannot be sure. But they did

happen. I know this because we watched them from the safety of our rented flat at 18 Sylvan Avenue, a large Victorian house right inside Dufferin Park.

We saw the police arrive in force to break up the combat and when the field was clear we tried to pick up what was left behind by the gangs. This included

what mother called “dirty things” left earlier under the forsythia bushes which bisected the park in those days. “Good balloons, Mum.”

So the disappearance of George Freeman passed unnoticed. I never met him even though he was a cousin. I do remember, however, Mom taking us by

street car to the Hunt Club Golf Course just before Christmas in 1944. Uncle Chris Freeman was the head greenskeeper and as such lived in a nice

little house in the centre of the place. I remember aunt Kitty crying cause someone had died. Uncle Chris who had a crooked eye was stoic but

serious. Normally he liked to tease us. Good humoured kind of man. But not that year. Mom explained that their son, George, has been declared

missing in acton. He was likely dead they knew but they clung to the hope he would turn up in a German POW camp when the war ended.

His bags were sent home from his 427 squadron headquarters at Skipton on Swale in Yorkshire. Seems I remember mom saying that aunt Kitty took

the suitcase up to George’s room and left it there. Unopened. She clung to the hope he would be found and return to them at war’s end. That hope

was held through 1945 and even into 1946 because newspaper reports of long lost soldiers and airmen continued to crop up. That room was waiting.

George Freeman became a kind of ghostly mystery figure to us. His room…his bag…were a kind of mysterious presence that entered the long term

storage of my brain. Even now, over 70 years later, I can visualize that greenskeepers house with aunt Kitty misty eyed and uncle Chris stoic.

A strange thing happened to me forty years after George Freeman died in that Halifax Bomber labelled HX 313. Something made me want to try and

find out what happened to George Freeman. I began to try to put the fragments of his life together in 1984. What really happened in the skies over

Belgium on May 27, 1944? As a history teacher at Parkdale Collegiate Institute I wanted my students to understand what it was like to be young, patriotic

and idealistic in the1940’s. Wanted the students of 1984 to see themselves wearing George’s fleece lined RCAF boots rather than just reading aging

historical facts. I had no idea just how startling the story would become.

Where to begin? Records existed, I knew that but I wanted to put flesh and blood on those records. So asked George’s sister Lillian, we called her Mickey

for some reason, if she had any letters sent by George from Yorkshire. She had a few letters and small pictures but she had no idea what happened

on that last day when HX 323 fell flaming from the skies over Bourg Leopold. Most moving was a picture of George in this RCAF uniform. He looked

so much like our own sons. Young. But also serious and perhaps idealistic.

INSERT PHOTO

to be continued

…the story is longer than I ever expected

These first few fragments became parts of what became a giant jig saw puzzle with many pieces missing and others in a jumble for me to sort. One piece dated January 4, 1944

was a starting point.

“Please accept my sincere sympathies in this period of great anxiety. I trust that favourable word will be forthcoming of your son. The enclosed letter (and snapshots)

addressed to you was found amongst your son’s personal effects. We regret the necessity of having to censor the letter for security reasons, and to ascertain if it contained

anything of a testamentary nature.” signed by Squadron leader Pennington of #6 Bomber Group

The snapshots turned out to be wonderful clues. The letter, George’s last letter, revealed that he knew his chances of survival were slim. He was taking extra flights to try and get

his 20 flights over with. Air crews who survived 20 bomber raids were relieved of future raids unless they volunteered to continue these risky flights which many did even with

the horrific death rates. George was planning to stop it seemed although that was not certain. He was committed to the war effort. But would he continue with HX 313?

Maybe not for he had fallen in love with an English girl ands preparing to surprise aunt Kitty with an engagement announcement. “The girl works in our mess and is a good girl.

In fact, mom, she is a Cockney, so you have an idea from that what she is like. Her parents made me very welcome and I had two eggs there.” Included with the letter was a

snapshot of George and his girlfriend in each others arms. Smiling. We would never know her name. Tragic romances were all too common among members of #6 Bomber Group.

INSERT PHOTO

George also told his mom that he had bought her a Victory Bond. But he said nothing about the war or HX 313. One tiny photograph wa dated February 10, 1944, taken in front

of a flimsy looking barrack on which was printed “Moe, Pop, Bob, Wilf, Eric, Casey and Me”. No last names but enough hints to lead me deeper. As things turned out “Pop” became

the linchpin I needed to get all the pieces in place. Sorry for the mixed metaphor.

INSERT PHOTO

INSERT PHOTO

The final snapshot, taken after the war, showed wooden cross labelled ‘P.O. Freeman, G.F., RCAF, KS 28,5, 44, #J 88397”. George would not be returning To aunt Kitty and Uncle Chris.

INSERT PHOTO

Then I found a crumpled news clipping with the title “Nazi rockets Failed to stop Canadians” referring to George Freeman’s first flight in HX 313. A strong hint that the skies over

Germany were filled with rockets and flak and night fighters…and terror.

But I still knew nothing about the last flight of HX 313. George was the mid upper gunner in that lumbering Halifax bomber belonging to Tiger Squadron, RCAF. Efforts to get information from otters

failed because the Privacy Act forbade the release of crew members that survived the war. Strange. Must be some reason for this but I failed to know what reason. Lillian

Peers, George Freeman’s sister, told me that the pilot of HX 33 visited their golf club home after the war. “His name was Mallet and the meeting was very emotional for all of them.”

The story could have ended there were it not for the offer of a CBC Classified appeal. “At the sound of the beep, give your message…be sharp and specific”

“Eric Mallet, are you listening? You were the pilot of a Halifax bomber that was shot down over Belgium on the night of May 27, 1944. Your upper middle gunner was George Freeman,

my cousin, who was killed. I am trying to put together the details of his death.” Then I innocently mentioned the little snapshot of the pet Scotch Terrier sitting in George’s Air Force hat.

“I have a few fragments that belonged to George. One is an RCAF hat sitting upside down with a little black dog below which is written “Nooky, Squadron Leader”, perhaps that clue

might help.” Does the word have any meaning?”

Well the word certainly had meaning. Many listeners responded to let me know that Nooky referred to sexual activity of a casual nature. Mention of Skipton on Swale and #6 Bomber

Group and HX 313 along with Nooky resulted in a shower of puzzle pieces. Many clarified he meaning of Nooky. “Refers to sexual activity, Alan.” I should have known that and

had I known I would never have included it in a CBC radio broadcast that went clear across Canada from seas to sea to sea.

Several phone calls came immediately. Most were irrelevant. Veteran airmen just making contact…wanting to help. Mothers who had lost sons. Sisters who had lost brothers. One

man living in a dirt encrusted room on Toronto’s River Street was insistent I visit him. Doing so I realized he had lost the battle with alcohol long ago. He had been a gunner with

#6 Bomer Group but had never met George Freeman. He just wanted someone to talk to.

There was no call or letter from any of the four surviving crew members of HX313. But there was one unusual call. “Alan, my name is Joyce Inkster, a listener told me to call you and

offer my help. For the past few years my husband and I have been tracing and reassembling RCAF flight crews. Perhaps we can help you.”

The Inkster were part of the Allied Air Forces Reunion. Joyce Inkster was a female version of Sherlock Hollmes. Within a day she had found the casualty report for the night

of May 27/28, 1944. It listed when names of the crew and 1944 addresses. Pilot Eric Mallet was from Vancouver. Mrs. Inkster consulted her collection of telephone books from

around the world, No Mallet listed in Vancouver. “Let’s try Victoria” There was an E. Mallett. Was it worth a call…budget over run possible was in my mind. I could not afford to

call every Mallett in Canada. “Don’t worry, I have a system. I make the call when rates are low, say the message fast…of wrong person end the call in less than a minute. But first

I need a clue that will guarantee I’ve reached the right person.”

The Scotch Terrier picture…Nooky….almost barked at us.

“Are you Eric Mallett the pilot of HX 313 in 1944?”

“Yes,” My heart skipped a beat.

“Did you have a mascot?”

“Yes, we had a scotch terrier.”

The pilot of HX 313 had been found and the story began to unfold. I was asked to return the CBC Joe Cote show snd tell the audience the story as it stood.

We found the pilot of HX323 living in Victoria, British Columbia, talked with him…he confirmed that they had a mascot… Scotch Terrier Nooky.

“We had a seven man crew normally but on our last doomed flight we had an eight member. New pilots joining the squadron were assigned to a veteran pilot for

one live operations flight so we had co-pilot W.F. Elliott aboard. Of our eight man crew, 3 were killed but 5 managed to bail out.”

THE LAST FLIGHT OF HX 313 – LETTER FROM PILOT OFFICER ERIC MALLETT, 1984

Many Bombers featured ‘Blonde Bomber’ nose art. This photo of a Handly Page Halifax bomber

is likely not HX 313.

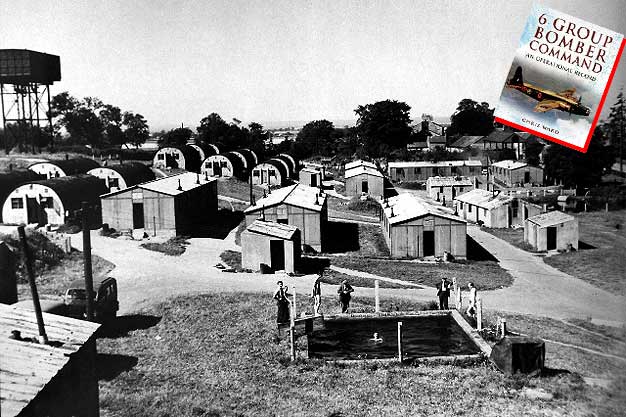

Picture of personal standing on wings of a Halifax Bomber at Skipton on Swale

Yorkshire, where George Freeman was stationed as a mid upper gunner on

HX 313, Number 427 Tiger Squadron, Number Six Bomber Group, RCAF.

“Dear Alan:

In the first place I must you that George Freeman was never known to us as George, he was Hank. Hank carried out his duties as Mid Upper Gunner

with great courage and at no time was overcome by fear. I am enclosing the only picture of our aircraft that I have with a member of the ground crew

sitting in my seat. The ‘Blonde Bomber’ was one of the finest aircraft that I have ever flown (note: Eric was an experienced pilot) At that time the Halifax

was the fastest heavy bomber in the world. We carried 42 tons of bombs and 21,000 gallons of100 octane gasoline, total all up weight was 85,000 pounds

Hank’sturret had four Browning machine guns capable of firing 1,250 rounds per minute.”

Note from 1984: Eric Mallett’s enthusiasm for the Halifax contrasted with the opinions of military historians who regarded the Halifax heavy bomber inferior to the Lancaster.

Some historians even went so far as to note that the conversion of bomber squadrons to Lancasters was done in a discriminatory manner which favoured

RAF bomber squadrons. Canadian Number Six Bomber Group continued to fly Halifax bombers to the end of the war.

“The member of my crew were Flight Lieutenant Bob Irwin (deceased); Wireless Operator Wilf Wakely (deceased); Vic Poppa, tail gunner; Ken Sweatman, bomb aimer;

Engineer Morris Muir (English); Mid-UpperGunner George Freeman (deceased); and flying officer Elliot who was coming along on his first trip…The target was Borg

Leopold in Belgium a base which the Germans were using as a rest camp for their troops from the Russian front. After leaving the briefing I mentioned to the

crew that we were being sent on a mission for the sole purpose of killing people. We carried 14,000 lbs. of anti-personnel bombs and the aiming point was to

be the officers quarters. This mission did not sit well with the crew. We had already been through some tough missions against industrial targets but

this mission made us feel uneasy.”

“Strangely enough we were not able to drop our load. We were right on our bomb run when we got hit. Just a few seconds prior to being hit I had an

urge to take evasive action but I did not because we had our bomb doors open and had started our run. I didn’t want to spoil the bomb aimers sighting

as there was no indication of an attack other than my hunch. Suddenly there was a tremendous burst of flame and I gave the order to ‘abandon aircraft ‘

immediately. Knew from past experience that we only had seconds to do so because 100 octane gasoline would blow up once the flames reached the

tanks. The Navigators position was right on top of the forward escape hatch. The whole crew was supposed to go out this exit so I would know when all

were out. They did not, however, because Bob Irwin couldn’t get the hatch open. The second pilot (Elliott) and engineer (Muir) took off the rear seat and

went out of the entrance hatch. I went forward to see how Bob was doing and by good fortune he was beginning to have some luck so I went back and

straightened out the aircraft. In what seemed like an eternity I returned to the hatch in time to see someone leaving. I then, did not hesitate to follow.

Upon hitting the air my flying boots left me and I then tried to find the rip chord on my parachute. I couldn’t find the ring for what seemed like another

eternity. Eventually I hooked the ring, otherwise I would not be here.”

Note: Even today, Oct. 2, 2019, I can remember reading Eric Mallett’s letter. Rivetting. I could hardly believe I had set an event like this in

motion back 1984. I had an idea that this was the end of the story so I read slowly and re-read even slower. But the story of the Last Flight

of HX 313 was really just beginning. Read on!

“Drifting down through the nigh sky, I could see the target with the bombs landing, exploding and setting fire to the buildings. I thought for a moment or two

that I was going to land right on it. The next thing I recall was seeing the ground come up to me and then ‘Boom!’…everything was silent. When I came

to, I found myself right beside a barbed wire fence. Remembered my previous training and buried my parachute. It required much effort.

“It is almost impossible to describe the feeling that overcame me. Since that day nothing has ever scored me as all I have do is recall in my

mind this dreadful night and the terrible feeling that I had.”

“I spent the rest of the night sitting in a cornfield taking off my rings and rank markings as well as looking at my purse and pandora. The escape kit

contained Horlicks tablets, benzedrine, German, Belgian And French currency. When daylight came I discovered that I was close to a small village.

I knew that i must get some help as I had a badly cut finger and no footwear. I waited and waited to see what sort of traffic was entering or leaving the village.

There seemed to be none other than that of someone tying up a goat close to where I was hiding, for quite long time I wondered what the tinkling of

the goat’s bell was.”

“Alan, I am going to sign off for now for this is only the beginning of a long, long story. Enclosed you will find your map with the location of the attack. Also

you will find pictures of my crew, and one of the Blonde Bomber. We were not allowed to take any pictures of our aircraft for security reasons, as you can

well understand. Also included is a picture of Hank and Vic Poppa engaged in a little horseplay outside of our flight room. Vic Poppa and Ken Sweatman

would be very pleased to hear from you if would care to write them.”

Kikndest Regards

Eric L. Mallett

Note from 2019: Wow! What a letter. More to come. Eric Mallett included the addresses of two other survivors. The story was growing and growing. It could so easily have been

lost. What followed was almost a year of contacts back and forth and even a visit with Victor Poppa in Cslifornia topped off by him travelling to Toronto in a ramshackle truck

and trailer filled with spare used tires. Victor’s story eventually took over. Hank’s best friend. Could I put their life experiences back together? Pictures are a bit of

a problem for me in 2019. They are here among my books and records but it will take time to find them. My priority is to get the written account transcribed to digital.

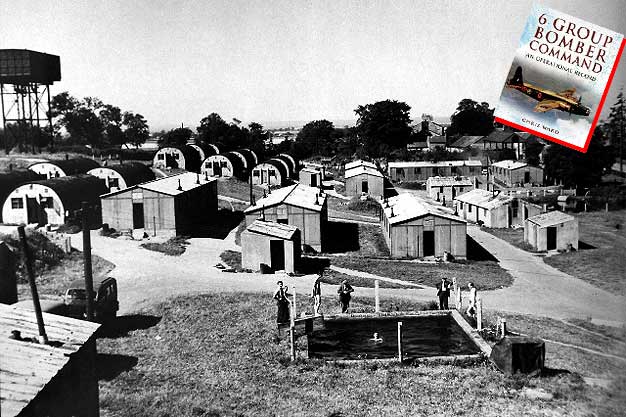

Note from 2019: This is the living quarters at airbase Skipton on Swale in 1944, a series of Quonset buildings with rounded roofs. The ruined brick building

was the operations centre, picture taken about 1984 when the airbase had been converted to a chicken farm after the tarmac landing strip had been

ripped up.

TO BE CONTINUED … TRANSCRIBING MY 1984 STORY NOW IN 2019…HOPE YOU ENJOY IT