S. O. S. The LYMAN M. DAVIS

Schooner Days CIII. (103)

“What a shame to burn that old schooner out at Sunnyside!” so many have protested to The Telegram, in letters and over the phone.

The Telegram thinks so, too.

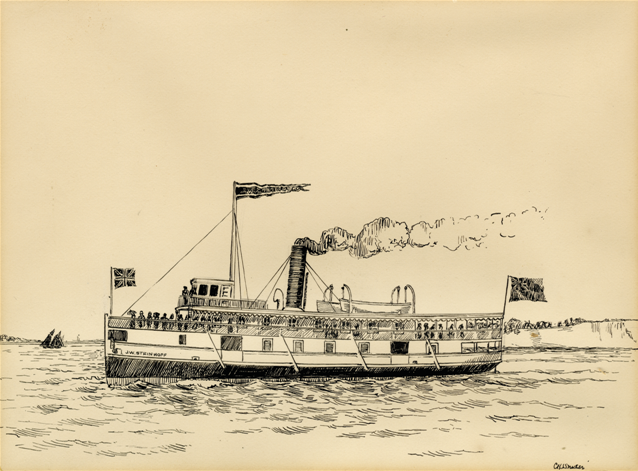

“That old schooner” is the Lyman M. Davis, of Kingston, built at Muskegon, Mich., in 1873, and now the last lake sailer left afloat.

That she is an “American bottom” is incidental. She is absolutely typical of the medium sized schooner of the Canadian and American fleets which queened it on the inland seas up to fifty years ago, thriving until the railways drove them under the horizon.

The Lyman M. Davis has been Canadian-owned for twenty years and traded out of Kingston under Captains McCullough and Daryaw up to last year. The “three links” on her stern symbolize her owners’ membership in the Order of Oddfellows; the stars, her American origin. In the absence of any corresponding original Canadian-built vessel she is the best possible example of one of the old wind-driven wooden walls which once girdled the Great Lakes. The small schooner, Shebeshkong, renamed, rebuilt, rerigged and equipped with engines, which went to Chicago this year from Midland, is neither original nor typical. She was once the North West, built in Oakville in 1882.

If Telegram readers want the Lyman M. Davis to be preserved The Telegram will help them to preserve her.

If enough readers respond, the old schooner may be rescued and presented to the City of Toronto for permanent preservation at the Exhibition Grounds; a marine museum whose first function will be to demonstrate the patriotism of the water-loving citizens of Toronto in Centennial Year. The Lyman M. Davis would make a grand nucleus for a pageant representing a hundred years of water transportation in which Toronto has grown from a marshy bay to a ocean port.

This is not an “appeal.” The public is sick of “appeals.”

It is a straightforward offer of an opportunity to give evidence of the amount of earnestness behind the utterance of protests—with which The Telegram heartily agrees-against the wanton destruction of the last remaining sailing vessel on the Great Lakes.

The Telegram will receive and acknowledge any expressions of opinion addressed to “Schooner Days” in care of this paper.

If you want to save the Lyman M. Davis from the bonfire, say so.

If money will do it, The Telegram is ready with the first $100 now. But it is not money that talks—yet. It’s expression of opinion.

My shoulders are still sore from the bruises of the metal collar of the diving dress, but Diver Dennis Coffey assures me that either the shoulders or the soreness will wear off. He has callouses on his own like the leathery parts of the soles of the feet. In spite of the soreness, let me say, from my own meagre experience, that diving, in the sense of going under water in a suit and remaining down there to see what you can see, is decidedly worth doing, and every able-bodied seaman or seawoman should jump at the chance and into the lake with the chance on.

One of those blistering hot afternoons recently Major D. M. Goudy shanghaied me for a submarine voyage outboard the good ship Lyman M. Davis, of Kingston.

Major Goudy, after the Elizabethan fashion which gave command of ships to generals, is the Lord High Admiral and Fire Marshal of the recreation division of the Harbor Commission’s fleet. Major Goudy has burned more ships at Sunnyside than Hector succeeded in doing before Troy. It was in the pious hope of saving the Lyman M. Davis from his torch that this compiler of Schooner Days ventured a fathom or so below the surface.

The Lyman M. Davis, as everybody knows, is the old black schooner which lies at Sunnyside pathetically proclaiming “Come Bid Me Farewell.”

Thousands — seven thousand to date — have performed that rite during the last few weeks. I don’t know who Lyman was. He is probably dead long since. The schooner named after him is the last commercial windmill left on all these Great Lakes which once boasted an argosy of a thousand sails.

If all in favor of saving her will speak up. Major Goudy can find the way. That is what he is good at.

This, however, digresses from the diving exploit. The pitch was bubbling in the seams (at least, it always does in story books with similar provocation) when we hove ourselves over the Lyman M. Davis’ rail. Diver Coffey was broiling bacon on the brass plates of his dried out diving suit with no other fire than the sunbeams. After our purpose was explained I was taken to the captain’s stateroom in the cabin of the schooner and given a pair of khaki trousers, a white woollen sweater and a very heavy pair of black woollen stockings.

While I changed into this gear the radio in the galley gave a concert from Buffalo. What a contrast to the sort of concert the first skipper of the Lyman M. Davis had when he changed his wet sea clothes in this very room, on coming off watch while she wallowed down Lake Michigan from her launching place at Muskegon! That was in 1873, when “Marching Through Georgia” and “Ella Ree” and “Darling Nelly Grey” were still “new” songs. This first skipper, whoever he was, had never heard of the telephone, nor dreamt of the radio, and the concert he would be listening to would be the scream of the souwester whirling the last remaining ashes of the great Chicago fire. The Lyman M. Davis was launched the second year after the old woman’s cow had kicked over the lantern and almost obliterated what Will Carleton called the Queen of the North and the West.

When I emerged on to the deck Mr. Coffey’s bacon was done to a crisp, and he could have boiled his namesake by sunpower if anyone had thought to provide a percolator. They hadn’t, so he laid out the suit for me to get into. It was a piece of heavy white rubber, rather like winter combinations made out of fire-hose, much patched at knees and elbows, and en-

tered through a neckband consisting of a copper hoop that would head-a barrel. Sleeves were complete down to mitts with thumbstalls, all in one piece, and legs went right down to the toes. I wondered, at the last moment, what would happen if I wore a hole in the heel!

By the time I was in the suit I knew what Shadrach, Meshach and Abednego felt like when they got that inside job stoking the burning fiery furnace. I don’t know any worse conductor of heat than rubber, and the suit had been in the sun all day. Mr. Coffey, however, conducted me to a steel ladder, and obliged with a wooden stool. While I sat looking enviously at the water he further obliged with a pair of shoes with thirty pounds of lead in the soles, and girded me with a belt shaped like an old cork lifebelt, only the “floats” were squares of lead. These added seventy-five pounds to my avoirdupois, and he capped my preparation for the bathroom scales by screwing on to the under-collar of the suit sections of copper, well set up with nuts and a monkey wrench. He then screwed on to the upper collar which these formed the copper helmet, until I looked like a Whitehall Lifeguard in a nightmare.

The helmet was roomy, but its weight, and what I had added in lead and copper, came down very heavy upon my graceful shoulders. My borrowed plumage—beyond the trousers, sweater and socks—weighed three hundred pounds, and I could just toddle to the steel ladder fastened to the concrete seawall where the Lyman M. Davis was moored.

Mr. Coffey gave a few final instructions and explanations, from which it appeared that the bottom was so soft it was hard to walk on, and other things equally difficult to follow. Before putting the head-piece on me he had given me a little black skullcap with ear phones attached. He now thrust into the hollow of my helmet a small telephone transmitter or mouthpiece, and snapped together connections with the insulated wire coiled around the 30-foot airline which trailed from where I would have worn my crest, had my helmet been that kind.

I thought of the days of old when knights were bold, and how they must have waddled to war with three hundred pounds of iron on back and front, and by this time Mr. Coffey was screwing the circular facepiece or plate-glass window into my helmet, and I was cut off from the outside world.

I heard the soft whish-wheeze of the air-pump, being worked slowly and carefully on the Lyman M. Davis’ rail, and someone whispered in my ear: “Can you hear me? How do you feel?” It was the pump-man, who had the other end of the telephone, and I promptly replied: “So hot that if you don’t let me out of this right away I’ll come out in smoke.”

Mr. Coffey promptly unscrewed my facepiece and gave me a welcome breath of fresh air, hot though it was. He suggested taking off the helmet and cooling it, while I should go down the ladder and dip in the lake up to my neck, and so cool the suit.

This I did, and it was delicious to feel the cold lake water all around me without being wet. Then I toiled up the ladder, and they bolted and screwed my copper headpiece on again, poured a bucket or so more water over it—was heating up in the sun while they fastened it—and down the ladder I again stumbled.

The crushing weight came off my shoulders as the suit inflated and once in the water I felt as buoyant as a breakfast food ad. There was a strong feeling of pressure from the air in the suit against my ribs, and I tried to knock open the pressure valve with the back of my head, so as to let some of it out. Didn’t do very well with that, so I told the pump man on the telephone I didn’t want so much. It was easy to converse with him, and sometimes he switched over to Major Goudy, so that we were having a threesome, they in the sun and I in the drink.

I didn’t notice when I got under water. The schooner was moored where it wasn’t very deep. I just came to the end of the ladder, about four feet below the surface, and then let go. The first thing I noticed, when I began to look around in the twilight of the lake, was the length and prettiness of the weeds growing on her. They are not as long as the weeds taken off the R.C.Y.C. launch, Kwasind, recently, but they are rather neat flat grassblades with rippled edges, and looked well, viewed close up. Below them the bottom planks of the schooner are quite bare, for, unlike yachts, schooner bottoms were seldom or never painted. They were intended to float for years without drydocking, and no ordinary paint will last for long under water. Schooner bottoms were sometimes slushed with hot oil or Stockholm tar—”stock ellum tar,” the boys used to call it—before launching, and the smaller hookers sometimes painted all the way across the bottom after the spring scraping, but vessels like the Lyman M. Davis were usually as unpainted as a wharf below the light waterline.

The seams of the planks, where the oakum had been horsed in by caulking irons and mallets sixty years before, had been “paid” or filled flush with the surface, with tallow or white lead, and this paying showed white and clean. The work Diver Coffey had been doing under water, recaulking all the seams where the oakum showed signs of “crawling” or coming out, was also discernible.

When I patted her oaken forefoot with my rubber mitt it sent a thrill through my diving helmet to realize I was stroking a piece of timber that had ploughed 590,000 miles of lake water. Calculate it for yourself. The schooner was launched in 1873 and was sailing every year up to the end of 1931; fifty-nine seasons. Even a sluggish schooner would average three hundred miles each week of the sailing season. That would be ten thousand miles for thirty weeks or so each year. Five hundred and ninety thousand miles! Almost twenty-four times round the world. A long, long cruise —even if the wheeze of pumped air in my ears made mental arithmetic with me a far from exact science.

Not all of the schooner’s bottom could be explored, because she was lying in too shoal water to permit crawling under her—at least I couldn’t, for I do not know enough about moving in a diving suit. There are things you mustn’t do, such as getting your air-valve down, and things Mr. Coffee can do, such as bloating himself up by closing the air-valve and increasing his buoyancy until he shoots out of the water— these I couldn’t attempt.

Besides, the soft silt at the bottom let my 30-lb. soles sink in until I was in mud to the knees, and the fouled water clouded so that I could see nothing. I remembered with interest , the wagon and team of horses that disappeared in the quicksand of the lake shore years ago, but it was too late to go looking for them.

From what I could see of the bottom of the Lyman M. Davis it was apparent that she was sound enough to last indefinitely if she is retained as a museum of lake lore. She does not appear to need drydocking, although some of her seams will certainly benefit by Diver Coffey’s caulking iron. Her planking is not much scraped and scarred by grinding on beaches. She has been drydocked, of course, at intervals during her sixty years of service, but it is a long time since she was last out. Still, she is cleaner than one would expect, and appears to be quite sound below.

“All right, I’m coming up,” I told the pump man, and could hear him tell the diver. Mr. Coffey had all the time carefully watched my airline, the heavy rubber hose which fed my nostrils, and also my lifeline, the light rope which encircled my waist.

I had been keeping these together in lone rubber-mittened hand, but he I had been saving me the trouble. I had less difficulty getting on to the ladder than I expected, a knee at a time and then a foot at a time, but I became very “heavy” to my own feeling, as I emerged from the water and took the weight of the suit on my sore shoulders. They helped me out on to the seawall—and it was glorious to drink in the fresh air again.

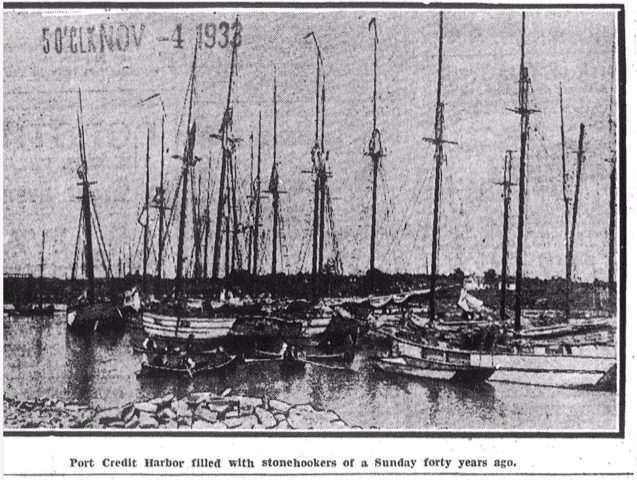

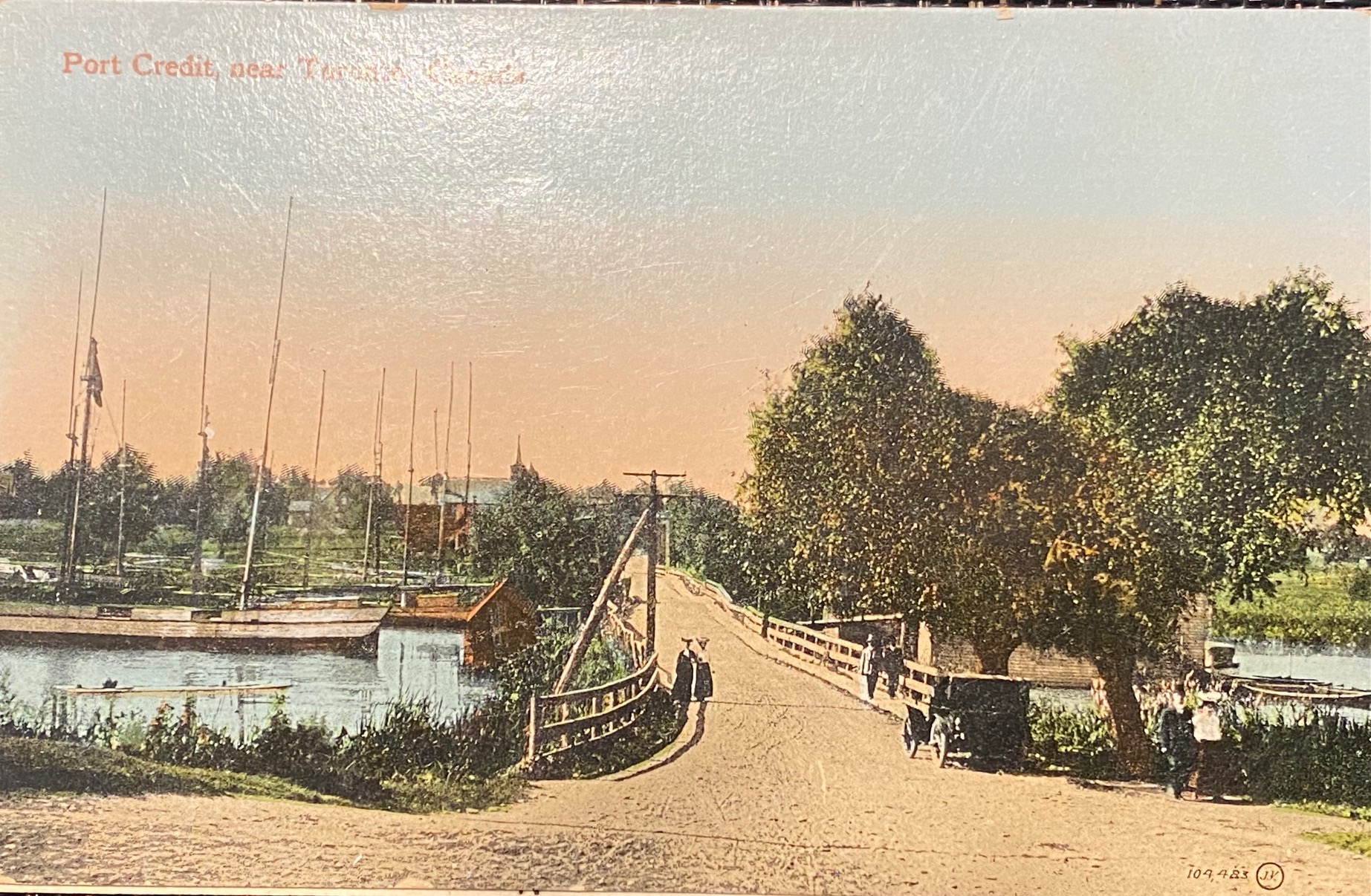

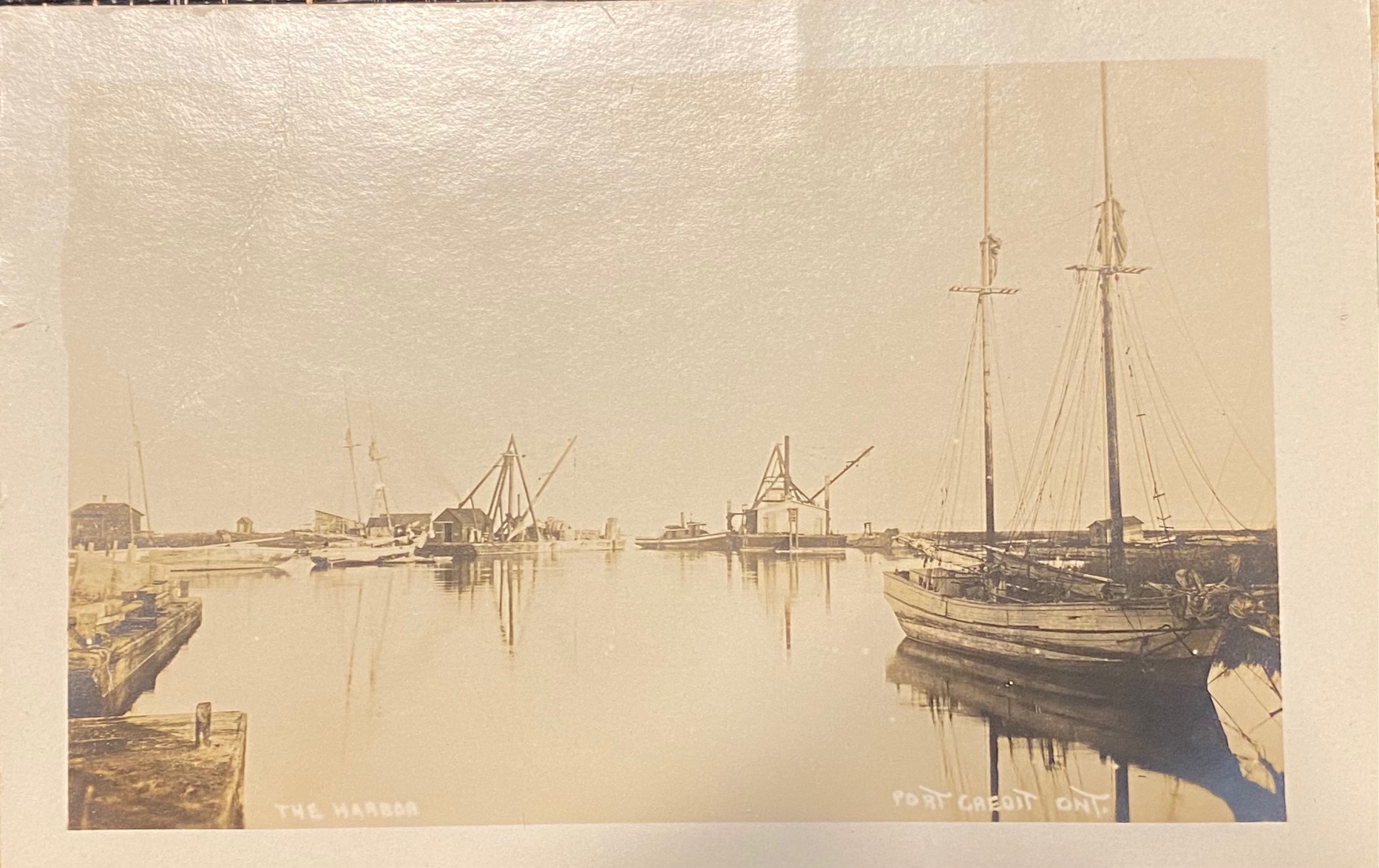

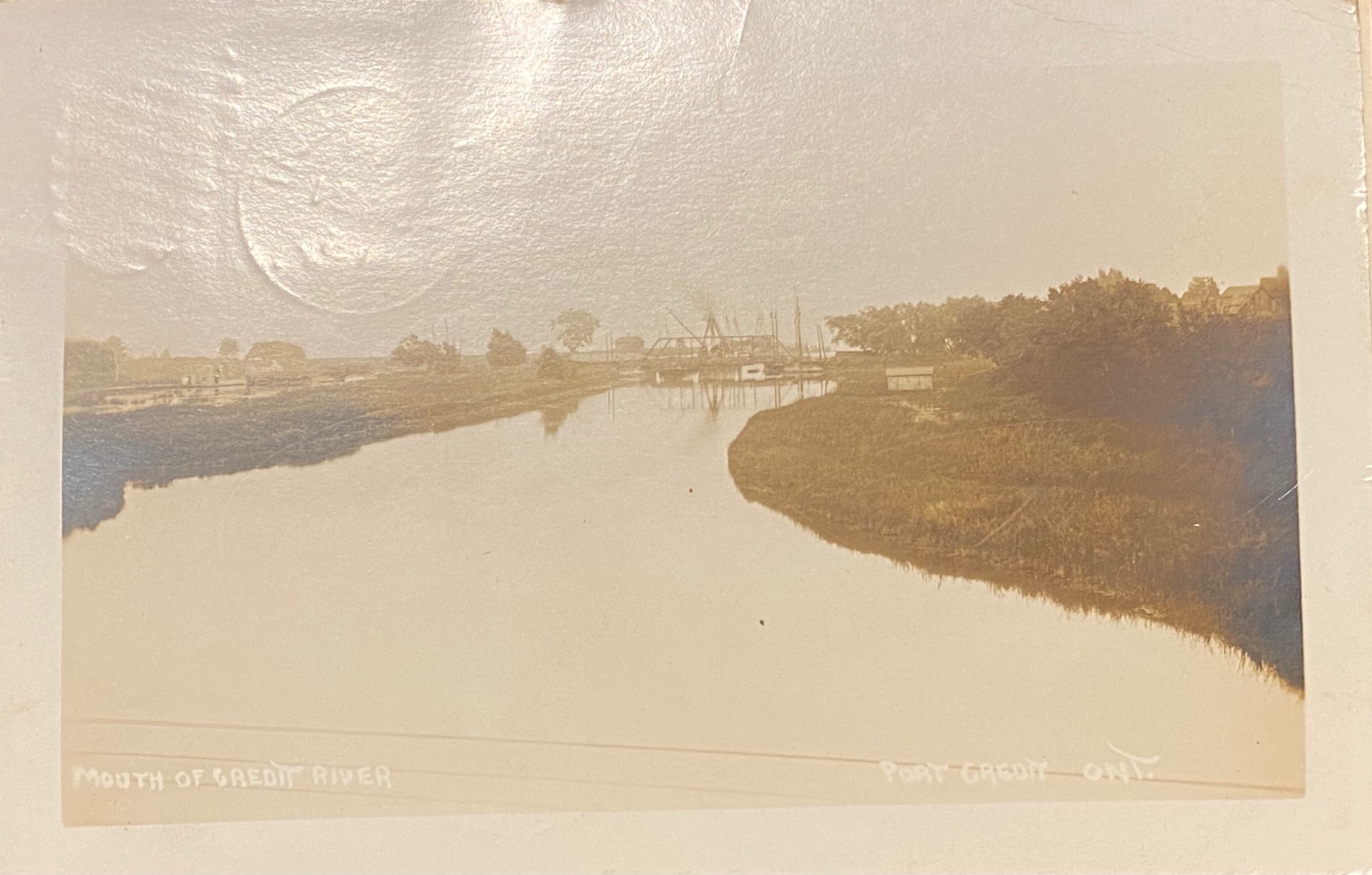

heritagemississauga.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Port-Credit-Harbour-Scene-Stonehooker-in-harbour-1908-Harold-Hare-Image-300×204.jpg 300w,

heritagemississauga.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Port-Credit-Harbour-Scene-Stonehooker-in-harbour-1908-Harold-Hare-Image-300×204.jpg 300w,  heritagemississauga.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Unknown-People-Stonehookers-of-Port-Credit-300×182.jpg 300w” sizes=”(max-width: 723px) 100vw, 723px” apple-inline=”yes” id=”A89B2CCD-4CB9-4A03-81A7-3DF23D292D45″ src=”http://alanskeoch.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Unknown-People-Stonehookers-of-Port-Credit-1.jpeg”>

heritagemississauga.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Unknown-People-Stonehookers-of-Port-Credit-300×182.jpg 300w” sizes=”(max-width: 723px) 100vw, 723px” apple-inline=”yes” id=”A89B2CCD-4CB9-4A03-81A7-3DF23D292D45″ src=”http://alanskeoch.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Unknown-People-Stonehookers-of-Port-Credit-1.jpeg”> heritagemississauga.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Sailors-Port-Credit-Harbour-with-stonehooking-scow-undated-300×234.jpg 300w” sizes=”(max-width: 641px) 100vw, 641px” apple-inline=”yes” id=”03FF66DA-2E12-4EA4-87C4-8387A4160897″ src=”http://alanskeoch.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Sailors-Port-Credit-Harbour-with-stonehooking-scow-undated.jpeg”>

heritagemississauga.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Sailors-Port-Credit-Harbour-with-stonehooking-scow-undated-300×234.jpg 300w” sizes=”(max-width: 641px) 100vw, 641px” apple-inline=”yes” id=”03FF66DA-2E12-4EA4-87C4-8387A4160897″ src=”http://alanskeoch.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Sailors-Port-Credit-Harbour-with-stonehooking-scow-undated.jpeg”> heritagemississauga.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Port-Credit-Harbour-Stonehooker-Lillian-and-Harbour-Dredge-c1900-300×215.jpg 300w,

heritagemississauga.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Port-Credit-Harbour-Stonehooker-Lillian-and-Harbour-Dredge-c1900-300×215.jpg 300w,  heritagemississauga.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Stone-Hooker-Lillian-Port-Credit-Harbour-c1914-300×210.jpg 300w,

heritagemississauga.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Stone-Hooker-Lillian-Port-Credit-Harbour-c1914-300×210.jpg 300w,